Starship re-entry temperatures stainless steel performance is one of the most controversial and fascinating engineering challenges in modern spaceflight. What if the most powerful rocket ever built didn’t fail on launch, but instead burned up while coming home? That shocking possibility explains why SpaceX’s Starship must survive re-entry temperatures above 1,400°C, a heat intense enough to melt many metals. Even more surprising is SpaceX’s bold decision to build Starship primarily from stainless steel, a material many critics once called outdated. Is this choice a brilliant engineering breakthrough or a dangerous compromise that could threaten future missions to the Moon and Mars?

That question is now at the center of global attention, especially as Starship moves closer to operational flights that could reshape space travel, satellite deployment, and even point-to-point travel on Earth.

Why re-entry heat above 1,400°C is unavoidable

When Starship slams back into Earth’s atmosphere at orbital speeds of nearly 27,000 km/h, it doesn’t heat up because of friction in the simple sense most people imagine. Instead, the air in front of the vehicle compresses so violently that it forms superheated plasma. Temperatures around the spacecraft can soar beyond 1,400°C, rivaling the heat inside industrial furnaces.

This extreme thermal environment lasts for several minutes. During that time, Starship must protect not only its structure but also its fuel tanks, avionics, and—eventually—human passengers. A small failure in thermal protection can escalate quickly, as history has tragically shown with earlier spacecraft.

For SpaceX, surviving this heat isn’t optional. Starship is designed to be fully reusable, flying dozens of times. That means it must endure re-entry again and again without becoming dangerously fragile or prohibitively expensive to refurbish.

The stainless steel surprise that shocked the industry

Most modern rockets rely on lightweight aluminum alloys or advanced composites. SpaceX deliberately went in the opposite direction. Starship uses 300-series stainless steel, a material better known for kitchen equipment than interplanetary spacecraft.

At first glance, this seemed like a risky and even backward move. Stainless steel is heavier than aluminum and carbon composites. Extra mass usually means less payload to orbit, which sounds like a negative tradeoff. However, the story changes dramatically under extreme heat.

Stainless steel retains much of its strength at temperatures where aluminum would weaken or fail. While aluminum begins losing structural integrity around 300–400°C, stainless steel can tolerate temperatures approaching 1,500°C. That margin matters enormously during re-entry, when safety depends on predictable behavior under thermal stress.

There’s also a practical advantage that directly affects people’s lives and the space economy. Stainless steel is far cheaper and easier to manufacture than aerospace-grade composites. This cost reduction supports SpaceX’s long-term goal of lowering launch prices and increasing access to space for scientific research, communications, and global internet coverage.

Brilliant engineering or dangerous gamble?

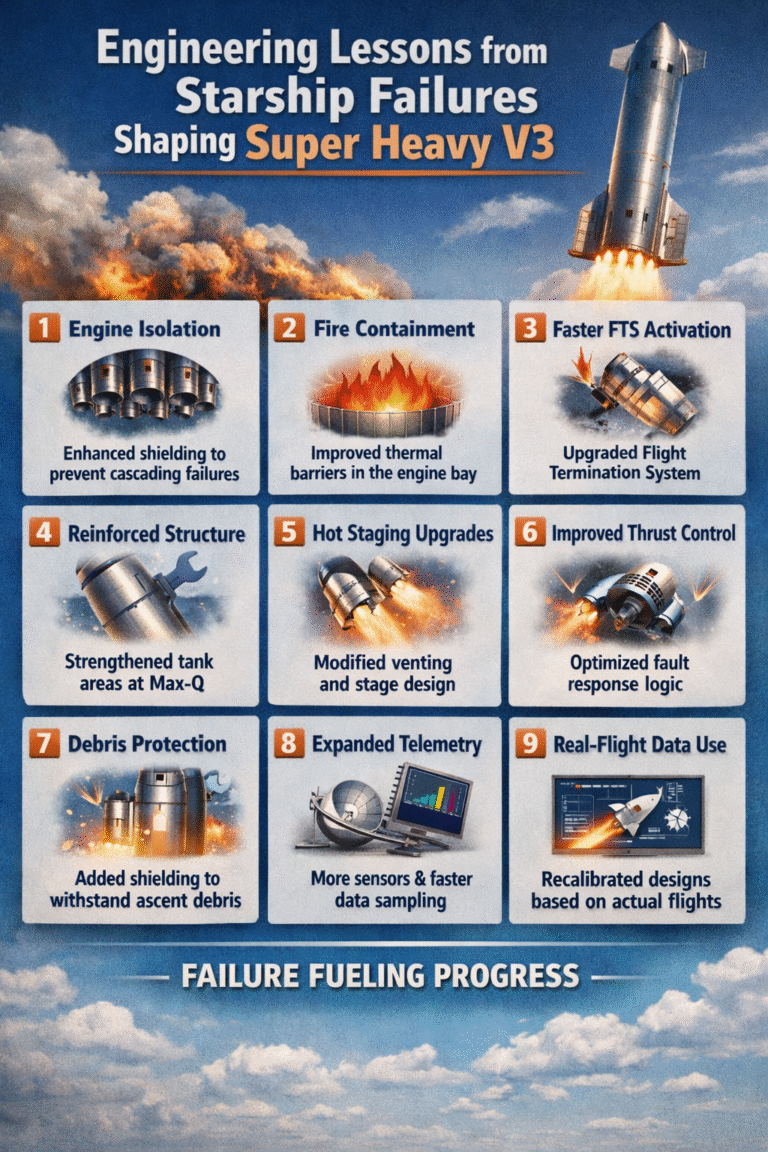

Calling stainless steel a purely brilliant choice would ignore the real risks. Heat resistance alone does not guarantee survival. Starship still relies on thousands of heat shield tiles on its leeward side to manage re-entry heating. These tiles must stay attached and intact through violent vibrations and rapid temperature changes.

Unlike the Space Shuttle’s fragile silica tiles, SpaceX is attempting a more robust system. Even so, tile loss or cracking remains a serious concern. Stainless steel may survive higher temperatures, but uneven heating can cause warping, stress fractures, or long-term fatigue if not carefully managed.

Another challenge is oxidation. At extreme temperatures, steel can oxidize rapidly unless protected, potentially weakening the surface over repeated flights. SpaceX is betting that clever design, active cooling in certain areas, and rapid iteration can manage these dangers.

This is where the gamble becomes clear. SpaceX is trading conventional safety margins for speed of development and radical reusability. That approach has delivered record-breaking launch rates with Falcon 9, but Starship operates on a far more extreme scale.

Why this matters beyond SpaceX fans

Starship’s success or failure will affect more than just Mars dreams. If stainless steel proves reliable under 1,400°C re-entry conditions, it could redefine spacecraft design across the industry. Cheaper, tougher vehicles could accelerate Earth observation, climate monitoring, and global communications.

For everyday people, this means faster innovation cycles, lower satellite costs, and potentially new transportation concepts like sub-orbital Earth-to-Earth travel. On the other hand, if the approach proves dangerous, it could slow progress and reinforce more conservative, expensive designs.

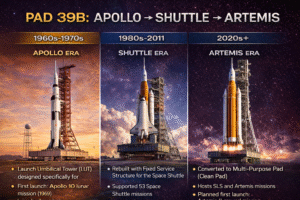

Agencies like NASA are watching closely, especially as Starship is central to future lunar missions. You can already find technical background on atmospheric re-entry physics on NASA’s official site, and SpaceX regularly shares Starship updates and test results on its own platform—both valuable external references for readers wanting deeper insight.

A bold future forged in heat

Surviving 1,400°C re-entry temperatures is not just an engineering requirement; it’s a symbol of SpaceX’s philosophy. Stainless steel represents a willingness to challenge assumptions, accept visible failures, and iterate toward a breakthrough. Whether this choice proves ultimately brilliant or dangerously optimistic will be decided not by opinions, but by fiery returns from orbit.

One thing is certain: every successful re-entry brings humanity closer to a future where spaceflight is not rare, but routine.

If you found this deep dive eye-opening, share it with fellow space enthusiasts, drop your thoughts in the comments, and follow for more science-backed insights into the rockets shaping our future 🚀

FAQs

Why does Starship experience temperatures above 1,400°C during re-entry?

Because it re-enters Earth’s atmosphere at orbital speeds, compressing air into superheated plasma that transfers extreme heat to the vehicle.

Why didn’t SpaceX use aluminum or carbon composites instead?

Those materials lose strength at much lower temperatures, making them riskier for repeated high-heat re-entries.

Is stainless steel heavier than traditional rocket materials?

Yes, but its heat resistance and low cost offset the mass penalty in a fully reusable design.

Could stainless steel fail after multiple re-entries?

Repeated thermal cycling and oxidation are risks, which SpaceX is addressing through design iteration and testing.

Does this technology affect future human missions?

Absolutely. Reliable high-temperature survival is essential for safe crewed missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.