When SpaceX’s Starship descends from the sky, its stainless-steel body glowing orange from reentry heat, something feels oddly incomplete. The vehicle performs one of the most daring maneuvers ever attempted by a spacecraft—falling belly-first through the atmosphere, bleeding off speed using nothing but drag, then flipping upright at the last possible second and igniting its engines just meters above the ground.

And yet, there are no visible landing legs.

For decades, landing legs have been a visual symbol of precision rocketry. Apollo’s Lunar Module stood proudly on four spindly legs. Falcon 9’s boosters touch down on deployable carbon-fiber feet. Even small suborbital rockets rely on legs to absorb landing forces.

So when SpaceX’s most ambitious spacecraft appears to land directly on its engine skirt—or in some cases, crashes while attempting to—it naturally raises questions. Is this an unfinished design? A risky shortcut? Or something far more intentional?

The answer reveals a radical shift in how rockets are meant to operate—not as fragile, mission-specific machines, but as industrial vehicles designed for mass transport between planets.

The Question Isn’t “Why No Legs?” — It’s “Why Ever Have Legs at All?”

To understand why Starship currently lacks landing legs, we need to step away from traditional rocket thinking.

Historically, rockets were built like precision instruments. Each one was unique, expensive, and disposable. When reusability entered the picture with Falcon 9, landing legs became a necessary compromise. Falcon 9 boosters weigh around 25 tonnes empty, stand 70 meters tall, and return to Earth after traveling at nearly Mach 6 during reentry. Landing legs allowed SpaceX to recover these boosters safely without needing specialized ground infrastructure.

But Starship is not an evolution of Falcon 9. It is a rejection of its design assumptions.

Starship, when fully stacked with its Super Heavy booster, stands 120 meters tall, making it the tallest rocket ever built. The Starship upper stage alone is about 50 meters tall and is designed to carry up to 150 metric tons of payload in its reusable configuration. Fully fueled, the system holds approximately 4,600 tons of propellant, most of it liquid oxygen and methane.

Designing landing legs for a vehicle of this scale is not a simple extension of Falcon 9’s approach. It introduces a cascading set of problems that conflict directly with SpaceX’s long-term goals.

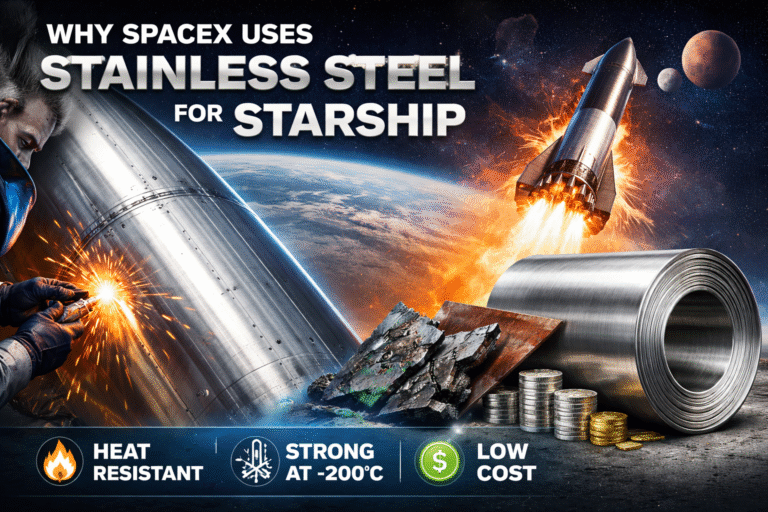

Mass Is the Enemy of Reusability

In rocketry, mass is unforgiving. Every kilogram added to a spacecraft is a kilogram that cannot be payload, fuel, or structural margin.

Landing legs are deceptively heavy. Falcon 9’s landing legs add several hundred kilograms, and that’s on a vehicle an order of magnitude smaller than Starship. Scaling that system up to Starship’s mass and height would likely require several tons of reinforced structures, hinges, actuators, and shock absorbers.

Those tons would fly on every mission—even missions where landing legs are unnecessary, such as orbital refueling or space-only operations.

For a spacecraft intended to fly hundreds or thousands of times, that mass penalty compounds brutally. A five-ton landing leg system could reduce payload to orbit by several tons every single flight. Over hundreds of launches, that translates into thousands of tons of lost cargo capacity.

SpaceX’s philosophy is ruthless efficiency. If a component does not directly support the long-term mission, it does not belong.

The Mars Problem: Uneven Ground and Unknown Terrain

Landing legs make sense when you know where you are landing.

Mars makes that assumption dangerous.

Unlike Earth, Mars has:

- Uneven terrain

- Dust layers of unknown depth

- Rocks that can exceed half a meter in size

- Gravity only 38% of Earth’s, altering load dynamics

A traditional landing leg system would need to handle all of this while supporting a vehicle taller than a 15-story building. The wider the stance, the heavier the legs. The stronger the legs, the more mass they add.

Now consider SpaceX’s goal: launching thousands of Starships to Mars.

Even a 1% failure rate due to landing instability would be catastrophic at that scale. SpaceX is not interested in designing landing legs that might work. They want a system that works every time, with minimal complexity and minimal mass.

Starship Is Designed to Be Caught, Not to Stand

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Starship’s design is that landing on legs is not the end goal.

SpaceX has been remarkably open about this: the ideal Starship landing involves no landing legs at all, because the vehicle is meant to be caught by the launch tower using mechanical arms known as “chopsticks.”

This concept was demonstrated successfully with the Super Heavy booster in 2024, when SpaceX caught a returning booster that weighed over 200 tons empty and was descending at significant velocity.

Catching a vehicle eliminates several problems at once.

First, it removes the need for heavy landing legs entirely. Second, it allows immediate placement back onto the launch mount, enabling rapid reuse. Third, it centralizes landing infrastructure at a controlled site, reducing risk.

In other words, instead of building complexity into every rocket, SpaceX builds complexity into the ground system—where mass does not matter.

This is a fundamental inversion of traditional aerospace thinking.

Why Not Temporary Legs During Testing?

A reasonable question follows: if the final system involves catching, why not add temporary landing legs during testing?

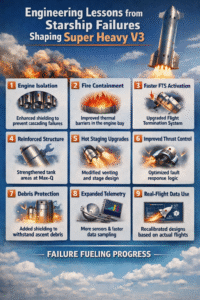

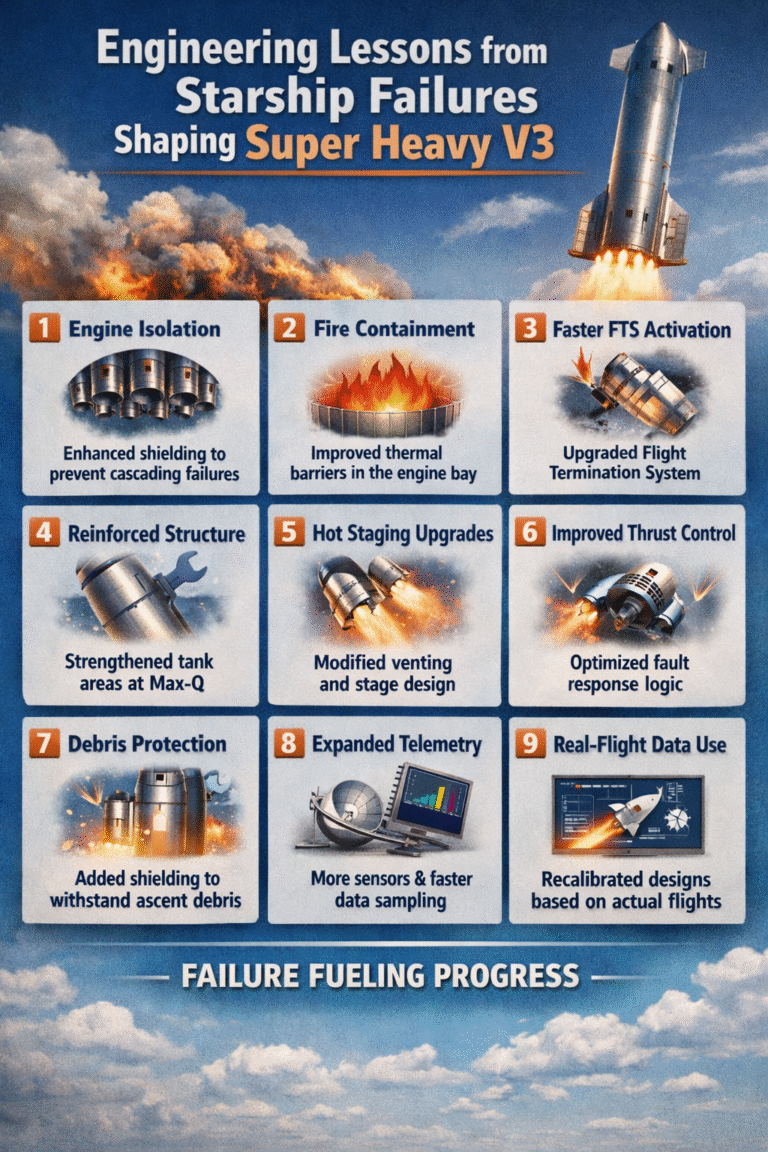

The answer lies in the development strategy SpaceX uses, which is radically different from traditional aerospace programs.

SpaceX follows a rapid iteration model. Starship prototypes are built quickly, tested aggressively, and replaced just as quickly. Many early Starship vehicles were never intended to survive long-term operations. They existed to answer specific questions: aerodynamics, engine relight timing, heat shield performance, control authority during belly flop.

Adding a complex landing leg system would slow development, introduce new failure modes, and distract from the primary objectives of early flight tests.

In other words, SpaceX would rather crash ten prototypes and learn faster than build one overly cautious design that delays progress by years.

The Engine Skirt as a Structural Solution

Another key insight is that Starship’s lower section—the engine skirt—is already one of the strongest parts of the vehicle.

Starship uses Raptor engines, each producing up to 230 tons of thrust. The thrust structure that holds these engines must withstand enormous forces during launch. That same structure can, in principle, tolerate significant loads during landing or catching operations.

Instead of distributing landing loads through legs, SpaceX concentrates structural strength where it already exists. This reduces redundancy and simplifies the overall design.

It also aligns with Starship’s cylindrical shape, which is optimized for internal pressure and structural efficiency.

The Heat Shield Complication

Starship’s heat shield covers much of its leeward side with over 18,000 ceramic tiles. Any landing leg system would need to avoid interfering with this delicate thermal protection system.

Falcon 9 does not face this issue because it does not experience full orbital reentry heating. Starship does.

Deployable legs would require cutouts, hinges, and moving parts in precisely the area where Starship needs uninterrupted thermal protection. This increases risk, increases maintenance, and complicates refurbishment.

For a vehicle meant to fly like an aircraft—with minimal inspection between flights—that is unacceptable.

Lunar and Mars Variants Will Be Different

It is important to clarify that Starship will eventually have landing legs, but not in the way people expect.

NASA’s Human Landing System (HLS) Starship, designed for the Moon, will use specialized landing structures suited for lunar gravity, dust conditions, and mission requirements. These legs will not be needed for Earth operations and will not fly back through Earth’s atmosphere.

Similarly, early Mars Starships may incorporate temporary landing aids until surface infrastructure is established.

But these are mission-specific variants, not the core Earth-launching Starship design.

SpaceX’s long-term plan is modularity: different configurations for different environments, without compromising the efficiency of the main system.

The Bigger Picture: Starship Is an Infrastructure Project

Perhaps the most important realization is that Starship is not just a spacecraft—it is part of an entire transportation ecosystem.

The launch tower, catching arms, orbital refueling tankers, and ground systems are all pieces of a unified architecture. In that architecture, landing legs are a legacy solution from an era when rockets were isolated machines.

SpaceX is building something closer to a spaceport, not a launchpad.

In aviation, airplanes do not carry their own runways. Ships do not carry their own docks. Trains do not bring their own stations.

Starship, ultimately, will not carry its own landing legs either.

Conclusion: No Legs Is Not a Bug—It’s a Statement

Starship has no landing legs yet not because SpaceX forgot them, but because they are questioning whether they should exist at all.

Every design decision reflects a future where spacecraft are:

- Rapidly reusable

- Mass-produced

- Operated at airline-like cadence

- Integrated into ground infrastructure

- Capable of moving humanity between planets

Landing legs solve yesterday’s problems. SpaceX is designing for tomorrow’s.

And if that means a few spectacular crashes along the way, SpaceX seems perfectly comfortable paying that price—for the chance to fundamentally change how humans reach space.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Will Starship ever have landing legs?

Yes, but only for specific mission variants such as lunar or early Mars landings. Earth-based Starships are expected to rely on catching mechanisms rather than traditional legs.

Why not use Falcon 9–style legs temporarily?

Falcon 9’s legs do not scale well to Starship’s size and mass. Adding them would significantly reduce payload capacity and complicate the heat shield and structural design.

Is landing without legs unsafe?

It is unconventional, but SpaceX mitigates risk by shifting complexity to ground infrastructure, where systems can be stronger, heavier, and more easily serviced.

Did SpaceX always plan to avoid landing legs?

Early concepts included legs, but as the design matured and the catching system proved viable, legs became increasingly unnecessary for Earth operations.

What about Mars, where there is no tower to catch Starship?

Initial Mars missions may use temporary landing solutions. Over time, SpaceX envisions building surface infrastructure to support safer and more efficient landings.