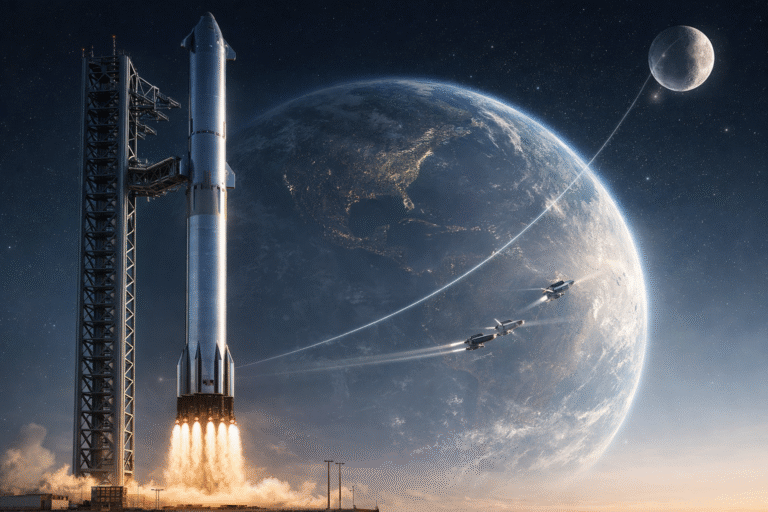

What if I told you that SpaceX’s gigantic Starship rocket cannot go to the Moon on a single tank of fuel—even though it’s the most powerful rocket ever built? 😲

That surprising fact sits at the heart of one of the boldest spaceflight strategies ever attempted: orbital refueling. It’s controversial, complex, and absolutely essential for humanity’s return to the Moon.

In this content, let’s unpack why Starship needs orbital refueling and approximately how many tanker launches are required for a lunar mission.

Why Orbital Refueling Is the Make-or-Break Factor for Starship

Starship is designed to be fully reusable, capable of carrying more than 100 metric tons to low Earth orbit. On paper, that sounds more than enough for a Moon mission. But here’s the catch: getting to orbit is only half the journey.

To land astronauts on the Moon and bring them back safely, Starship must perform multiple high-energy burns after reaching orbit. These include traveling from Earth orbit to lunar orbit, descending to the Moon’s surface, lifting off again, and returning. All of that requires an enormous amount of propellant.

The problem? Physics doesn’t care about ambition.

If Starship were filled completely with fuel on the launch pad, it would be too heavy to reach orbit. This is known as the tyranny of the rocket equation, and even SpaceX can’t escape it. So instead, Starship launches nearly empty, reaches orbit, and then refuels in space—just like aircraft refuel mid-air on long missions.

Orbital refueling isn’t a luxury. It’s the only way Starship can function as a true deep-space vehicle.

How Orbital Refueling Actually Works in Practice

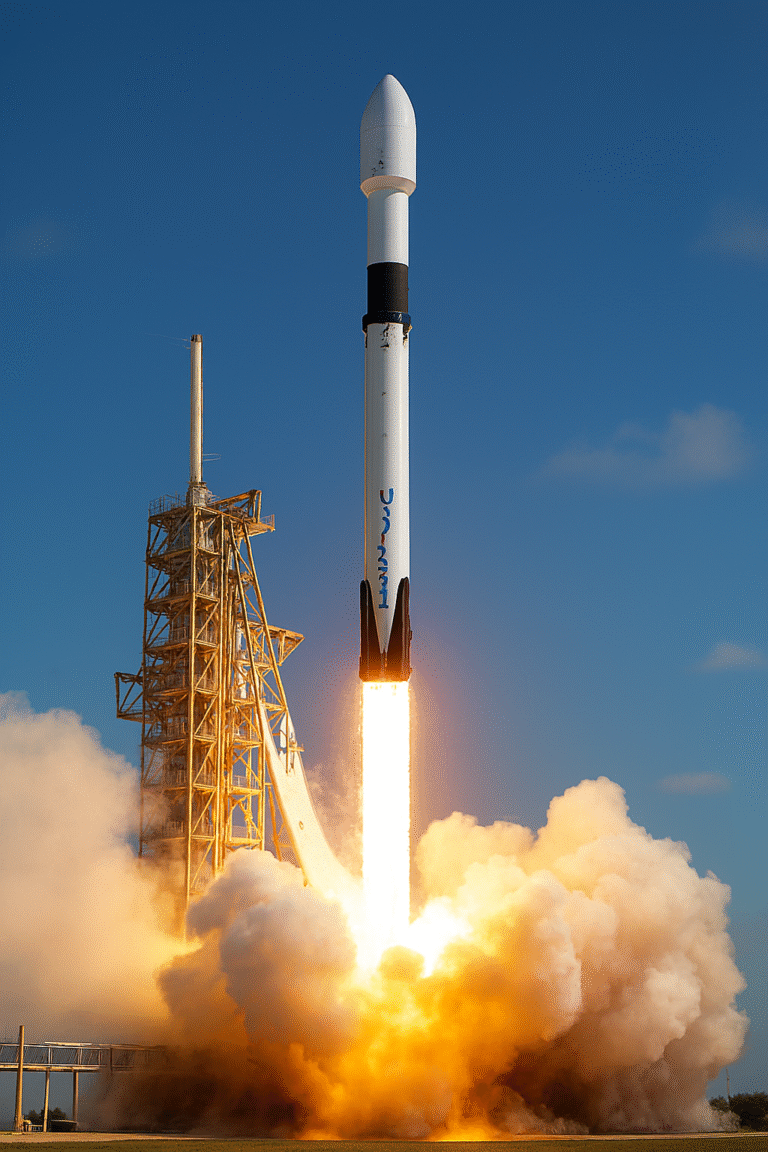

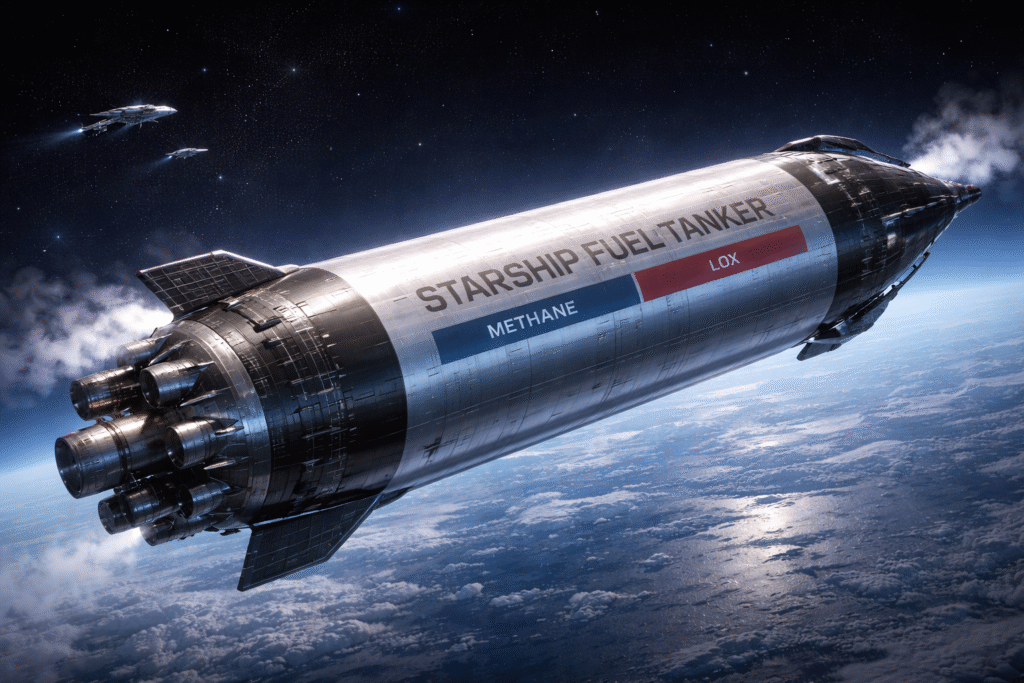

Once the lunar-bound Starship reaches low Earth orbit, it waits. SpaceX then launches a series of Starship tanker variants, each carrying super-cooled liquid methane and liquid oxygen. These tankers rendezvous with the lunar Starship and transfer fuel in microgravity—something never done at this scale before.

This technology is a cornerstone of NASA’s Artemis program, which selected SpaceX Starship as the Human Landing System (HLS). According to NASA’s official Artemis documentation, orbital refueling is not optional—it’s mission-critical.

(External reference: NASA Artemis program – nasa.gov)

So, How Many Tanker Launches Are Needed for a Lunar Mission?

Here’s where things get really interesting.

Based on current estimates from NASA and SpaceX insiders, a single lunar mission will require approximately 10 to 15 Starship tanker launches. Each tanker delivers only a fraction of the total propellant needed, and multiple dockings are required to fully fuel the lunar Starship.

The exact number depends on several evolving factors: how much propellant each tanker can deliver, how efficient the transfer process becomes, and how much margin NASA demands for crew safety. Early missions will likely sit at the higher end of the range.

Yes, that means up to 15 launches just to fuel one Moon landing.

It sounds excessive—until you realize SpaceX’s long-term plan is to launch Starship multiple times per week, dramatically reducing cost per flight. This is where Starship’s reusability changes everything.

Why This Matters Beyond SpaceX and NASA

Orbital refueling isn’t just about returning humans to the Moon. It fundamentally reshapes how humanity moves in space.

Once perfected, this technique allows spacecraft to launch lighter, cheaper, and more frequently. It opens the door to permanent lunar bases, Mars missions, and even space-based industries. For everyday people, this means faster innovation cycles, lower launch costs, and spin-off technologies that eventually reach Earth—just like GPS and satellite internet did.

If you’re following SpaceX closely, you’ll notice that Starship refueling tests are among the most critical upcoming milestones. Delays here affect Artemis timelines, international space partnerships, and the future of human exploration itself.

(Internal link suggestion: Read our detailed guide on SpaceX Starship missions: /spacex-starship-missions-explained)

The Risk and the Reward

Let’s be honest—orbital refueling is risky. Cryogenic fuel boils off, docking massive stainless-steel spacecraft is complex, and one failure can ripple through an entire mission architecture. Critics argue this approach adds too many moving parts.

But history favors bold solutions. Just as orbital rendezvous enabled Apollo moon landings, orbital refueling may be the breakthrough that makes deep-space travel routine rather than rare.

And if SpaceX succeeds, launching 10–15 tankers won’t feel shocking anymore. It’ll feel normal.

Final Thoughts: A New Era Fueled in Orbit

Starship’s need for orbital refueling isn’t a weakness—it’s a revolutionary strategy. By embracing complexity today, SpaceX is building a future where humans can travel farther, more often, and at lower cost than ever before.

If this technology works as planned, the Moon won’t be the end goal—it’ll be the first fueling stop.

👉 What do you think about orbital refueling? Is it a brilliant solution or an unnecessary risk? Share your thoughts in the comments and don’t forget to follow the chimniii.com for more deep-dive space explainers!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why can’t Starship go to the Moon without refueling?

Because launching with enough fuel for a full lunar round trip would make Starship too heavy to reach Earth orbit in the first place.

Is orbital refueling safe for astronauts?

NASA believes it can be, but early missions will be uncrewed to prove reliability before astronauts board the lunar Starship.

How many tanker launches are required for Artemis missions?

Current estimates suggest around 10–15 tanker launches per lunar mission, depending on performance and safety margins.

Has orbital refueling ever been done before?

Small-scale fuel transfers have occurred, but never at the scale Starship requires—this is largely uncharted territory.

Will this technology be used for Mars missions too?

Absolutely. Orbital refueling is essential for any realistic human mission to Mars.

If you found this article insightful, share it with fellow space enthusiasts and stay tuned—because the future of spaceflight is just getting started 🌌