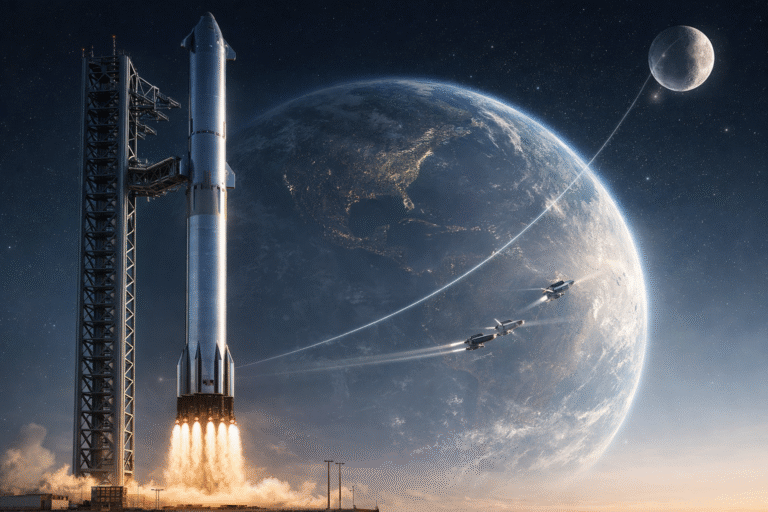

When SpaceX first revealed that its next-generation rocket would be built from stainless steel, the aerospace world reacted with disbelief. For decades, rocket design had followed a clear trend: lighter materials, advanced composites, and increasingly exotic alloys. Stainless steel sounded like a step backward—something better suited for kitchen appliances than interplanetary spacecraft.

Yet today, Starship’s towering stainless-steel body has become one of the most recognizable silhouettes in modern spaceflight. The choice was not accidental, nor was it a compromise. It was the result of ruthless engineering logic, grounded in physics, economics, and long-term vision.

To understand why SpaceX uses stainless steel for Starship, we must first understand what Starship is really trying to achieve—and why traditional aerospace thinking simply wasn’t enough.

Starship Isn’t Designed Like Past Rockets

Most rockets built over the last half-century were designed for a single goal: reach orbit once. Reusability, if considered at all, came later and usually at enormous cost. Materials like aluminum-lithium alloys and carbon composites were chosen primarily because they were lightweight, helping rockets squeeze out every last bit of performance.

Starship breaks away from this philosophy entirely. It is not meant to be flown once, refurbished extensively, and retired. It is meant to fly often, with minimal downtime, carrying enormous payloads, surviving violent atmospheric re-entries, and eventually landing on other planets.

That single change in mission philosophy reshapes every engineering decision—including material choice.

The Cryogenic Reality of Rocket Fuel

One of the least intuitive challenges in rocket design is temperature. Starship’s fuel tanks are filled with liquid methane and liquid oxygen, stored at temperatures hundreds of degrees below zero. At these cryogenic temperatures, many materials behave very differently than they do at room temperature.

Aluminum alloys, commonly used in rockets, actually become more brittle when chilled. Carbon composites can suffer from micro-cracking and complex failure modes that are difficult to inspect or repair.

Stainless steel behaves in the opposite way.

At cryogenic temperatures, stainless steel becomes stronger and tougher. This means the material can withstand higher stresses without cracking, even when the tanks are full of super-cold propellant and under immense pressure. For a vehicle as large as Starship, this property is invaluable.

It allows thinner walls, greater structural margins, and improved safety during fueling and flight.

Re-entry Heat: Where Stainless Steel Shines

Re-entering Earth’s atmosphere at orbital speeds is one of the most extreme environments any machine can survive. Temperatures can exceed 1,400 degrees Celsius, hot enough to weaken or destroy many aerospace materials.

Traditional rockets avoid this problem by not coming back at all. Capsules use ablative heat shields that burn away. The Space Shuttle relied on fragile ceramic tiles bonded to an aluminum frame—tiles that required painstaking inspection after every mission.

Stainless steel changes the equation.

Unlike aluminum, which rapidly loses strength at high temperatures, stainless steel retains much of its structural integrity even when heated intensely. This allows Starship to survive re-entry with a simpler, more forgiving heat shield system.

If a heat shield tile is damaged or lost, the steel underneath can tolerate brief exposure without catastrophic failure. That single fact dramatically improves Starship’s robustness and reusability.

The Cost Advantage No One Talks About Enough

Aerospace engineering has always been expensive, but Starship aims to lower costs by orders of magnitude, not percentages. This makes material economics just as important as performance.

Stainless steel is dramatically cheaper than aerospace-grade aluminum or carbon composites. It is widely available, easy to source, and does not require specialized autoclaves or curing processes. It can be welded, cut, and reshaped with relatively simple industrial tools.

For SpaceX, this means faster prototyping, faster iteration, and lower risk when designs change—as they often do in an experimental program.

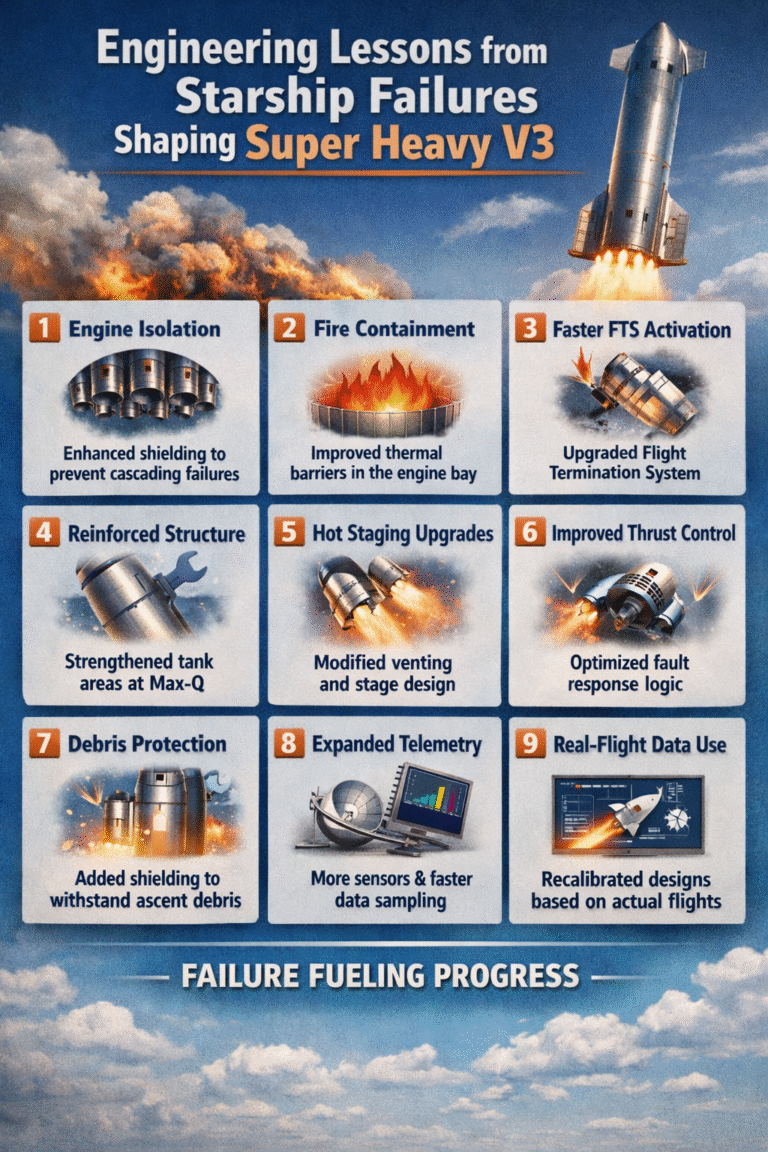

Instead of spending years perfecting a design on paper, SpaceX can build, test, fail, and rebuild at a pace traditional aerospace programs cannot match.

Manufacturing at Scale: A Hidden Superpower

Starship is not being built as a handful of handcrafted vehicles. SpaceX ultimately plans to produce hundreds of Starships. At that scale, manufacturing efficiency becomes a mission-critical concern.

Stainless steel enables a production style closer to shipbuilding than traditional aerospace. Large steel rings can be rolled, stacked, and welded rapidly. Sections can be replaced without scrapping entire vehicles. Modifications can be introduced mid-production without retooling entire factories.

This flexibility allows SpaceX to improve Starship continuously, rather than locking into a single design for decades.

Structural Toughness and Damage Tolerance

Spaceflight is unforgiving. Micrometeoroids, debris, hard landings, thermal cycling—all impose stress on a vehicle. Materials that fail suddenly or invisibly are dangerous in such environments.

Stainless steel is forgiving.

It bends before it breaks. Cracks are easier to detect. Damage is often localized rather than catastrophic. For a spacecraft designed to land repeatedly on Earth, the Moon, and Mars, these traits matter enormously.

On Mars, in particular, repairability could be the difference between mission success and total failure. Stainless steel can be repaired using relatively simple tools—something composites cannot offer.

Why Not Carbon Fiber?

SpaceX initially explored carbon composites for Starship, and for good reason. Composites are extremely lightweight and strong. But they come with serious drawbacks.

They are expensive, slow to manufacture, and prone to complex failure modes that are hard to predict. They also perform poorly at high temperatures, requiring heavy thermal protection systems.

For a one-off spacecraft, composites might make sense. For a rapidly reusable, mass-produced interplanetary vehicle, they become a liability.

Stainless steel trades some mass efficiency for durability, simplicity, and speed—a trade SpaceX is willing to make because Starship’s massive engines can compensate for the weight.

Weight Isn’t Everything When You Have Power

One of the reasons stainless steel was dismissed for rockets in the past is weight. Steel is heavier than aluminum, and every kilogram matters in spaceflight.

But Starship is not a conventional rocket.

With dozens of Raptor engines producing unprecedented thrust, Starship has the raw power to lift heavier structures while still delivering enormous payloads to orbit. Instead of chasing extreme weight savings, SpaceX prioritized a design that could survive repeated flights and harsh environments.

In other words, Starship doesn’t need to be lightweight—it needs to be reliable and reusable.

Mars Changes Everything

The decision to use stainless steel makes even more sense when viewed through the lens of Mars.

Mars has extreme temperature swings, abrasive dust, radiation exposure, and limited infrastructure. A vehicle landing there must survive not just one mission, but potentially years of exposure before refueling and return.

Stainless steel resists corrosion, tolerates thermal cycling, and maintains strength across a wide temperature range. It is far better suited for long-duration planetary missions than delicate composite structures.

Starship is not optimized for Earth launches alone—it is built for a future where rockets operate far from home.

The Philosophy Behind the Choice

At its core, SpaceX’s stainless-steel decision reflects a broader philosophy: optimize for the full mission lifecycle, not just launch performance.

Traditional rockets maximize efficiency at liftoff. Starship maximizes survivability, reusability, and scalability. Stainless steel supports that philosophy better than any alternative currently available.

It is not glamorous. It does not look futuristic in the conventional sense. But it works.

And in engineering, working reliably matters more than looking advanced.

Final Thoughts: A Counterintuitive Masterstroke

The choice of stainless steel for Starship may seem strange at first glance, but it is one of the most rational decisions SpaceX has made. It enables rapid iteration, lowers costs, improves safety margins, and supports the long-term goal of making humanity multi-planetary.

In hindsight, it may be remembered as the moment rocket design stopped chasing perfection—and started chasing practicality.

Sometimes, the future isn’t built from exotic materials. Sometimes, it’s built from steel.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Why does SpaceX use stainless steel instead of aluminum?

SpaceX uses stainless steel because it performs better at cryogenic temperatures, retains strength during re-entry heating, and is cheaper and easier to manufacture than aluminum alloys.

Isn’t stainless steel too heavy for rockets?

Stainless steel is heavier, but Starship’s powerful engines compensate for the extra mass. The benefits in durability and reusability outweigh the weight penalty.

Why didn’t NASA use stainless steel before?

Earlier rockets lacked the thrust and reusability goals that make stainless steel practical today. Most were designed for single-use missions.

Does stainless steel reduce heat shield requirements?

Yes. Stainless steel tolerates higher temperatures, allowing Starship to survive brief heat exposure even if tiles are damaged.

Is stainless steel better for Mars missions?

Yes. Its resistance to temperature extremes, corrosion, and mechanical damage makes it well suited for long-duration planetary missions.

Will future Starships still use stainless steel?

Unless a dramatically better material emerges, stainless steel is likely to remain the core structural material for Starship