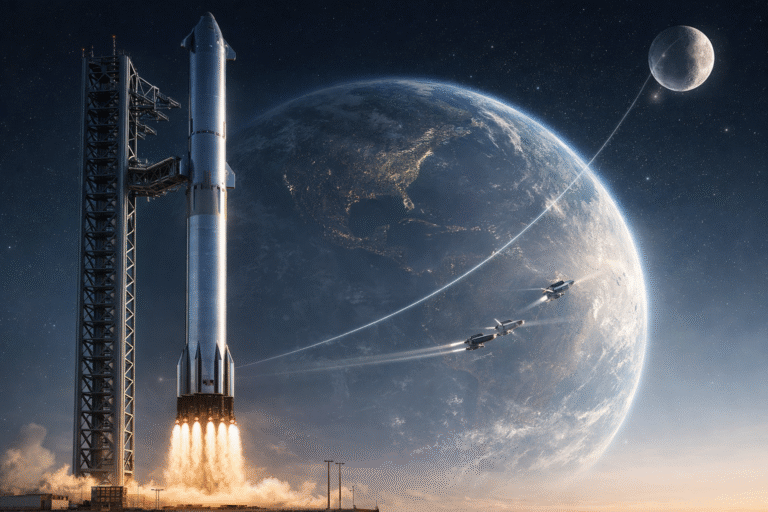

When people first see SpaceX’s Starship sitting on the Texas coast, the reaction is usually the same: That doesn’t look like a rocket.

It looks too shiny, too tall, too… unfinished.

And yet, this stainless-steel giant may turn out to be the most important machine humans have ever built.

Starship is not designed the way rockets have been designed for the last sixty years. In fact, almost every major engineering choice behind it breaks an old aerospace rule. The reason is simple: Starship is not meant to fly once. It is meant to fly again and again, carry enormous cargo, land on other worlds, and eventually make Mars reachable for ordinary humans—not just astronauts.

SpaceX’s Starship is often described as the most powerful rocket ever built, but raw power is only a small part of the story. What truly sets Starship apart is how it is engineered—from the materials used in its structure to the way it lands back on Earth. Understanding how Starship is designed helps explain why SpaceX believes it can dramatically lower launch costs, enable permanent lunar bases, and eventually transport humans to Mars.

To understand how Starship is designed, we need to forget what we think a rocket should be and instead follow the logic SpaceX is using from first principles.

Starship Is Not a Rocket — It’s a System

One of the most common misunderstandings is thinking of Starship as a single vehicle. In reality, Starship is a two-vehicle launch system working together as one machine.

At the bottom is Super Heavy, the booster that lifts everything off Earth. Sitting on top is Starship itself, which is both the upper stage and the actual spacecraft. Together, they stand about 120 meters tall, making Starship the tallest launch vehicle ever built.

This two-stage design exists because reaching orbit is brutally difficult. To stay in space, a vehicle must accelerate sideways to nearly eight kilometers per second. No single stage can do this efficiently while also being reusable. By splitting the job, Super Heavy provides raw power, while Starship handles orbital flight, re-entry, and landing.

What makes this system radical is that both stages are designed to come back and fly again. Not refurbished months later—reused rapidly, like aircraft.

The Stainless Steel Decision That Shocked Aerospace Engineers

If there is one design choice that defines Starship, it is the decision to build it from stainless steel.

For decades, aerospace engineers believed lightweight aluminum alloys or advanced composites were the only sensible materials for rockets. Stainless steel was considered too heavy, too old-fashioned, and unsuitable for flight.

SpaceX disagreed.

Stainless steel behaves in a way that is almost perfect for Starship’s mission. At extremely low temperatures—exactly the conditions inside a cryogenic fuel tank—stainless steel actually becomes stronger, not weaker. Aluminum does the opposite. During atmospheric re-entry, stainless steel can survive much higher temperatures before losing strength, reducing the need for thick heat shielding.

There is also a practical advantage that matters more than most people realize: stainless steel is cheap and easy to work with. When you are building dozens, then hundreds, of massive vehicles, material cost and repair speed matter as much as mass.

Starship accepts a small weight penalty in exchange for strength, heat tolerance, and manufacturability—and then overwhelms that penalty with sheer engine power.

How Starship Is Structurally Built

Starship is not built like a traditional rocket, and that difference directly explains why it does not rely on conventional landing legs. Instead of being precision-machined from countless custom parts, Starship is assembled from large stainless-steel rings stacked vertically and welded into a smooth, continuous cylinder. This manufacturing approach may look crude compared to legacy aerospace hardware, but it produces an exceptionally strong structure capable of carrying and distributing enormous loads without relying on external support systems such as deployable legs.

Inside the vehicle, two massive propellant tanks dominate the design. The lower tank stores liquid methane, while the upper tank holds liquid oxygen, with both tanks separated by a shared bulkhead—a single domed structure that acts as the ceiling of one tank and the floor of the other. By eliminating unnecessary internal structure, SpaceX reduces mass and concentrates strength along the vehicle’s central axis, precisely where landing and catching forces are meant to be absorbed.

These domed bulkheads and the surrounding thrust structure are engineered to survive extreme internal pressures, violent launch vibrations, and temperature swings ranging from cryogenic cold to the intense heat of atmospheric reentry. Crucially, this same reinforced lower structure is designed to tolerate vertical loads during landing or tower-catch operations, removing the need for wide, heavy landing legs that would add mass, complexity, and thermal vulnerabilities. In this way, Starship’s ring-stacked construction and shared-bulkhead architecture are not just manufacturing shortcuts—they are fundamental enablers of a legless landing philosophy.

This is not boutique aerospace craftsmanship. It is industrial-scale rocket building.

Why Starship Uses Methane Instead of Traditional Rocket Fuel

Fuel choice may sound boring, but it is one of the most important design decisions behind Starship.

Instead of kerosene or hydrogen, Starship runs on liquid methane and liquid oxygen. This choice solves several problems at once.

Methane burns cleanly, leaving far less residue inside the engines. That means engines can fly repeatedly without extensive refurbishment. Methane also offers excellent performance while being easier to store than hydrogen.

Most importantly, methane can be manufactured on Mars.

Using carbon dioxide from the Martian atmosphere and water ice from the soil, future missions can produce methane fuel directly on the planet. Without this capability, a Mars return mission would be impossible. Starship’s fuel choice is not about Earth launches—it is about coming home from another world.

The Raptor Engine: Why It’s So Difficult and So Important

At the heart of Starship is the Raptor engine, widely considered the most advanced rocket engine ever brought to flight.

Raptor uses a full-flow staged combustion cycle, meaning both the fuel and oxidizer are fully gasified and passed through turbines before entering the combustion chamber. This allows for extremely high efficiency and chamber pressure, but it also makes the engine incredibly complex to design and manufacture.

Why go through all that trouble?

Because this engine can produce enormous thrust while remaining reusable and durable. Starship needs engines that can ignite dozens of times, survive violent landing maneuvers, and operate reliably in deep space.

Super Heavy uses thirty-three Raptors arranged in a dense cluster, creating a level of thrust never before seen. Starship itself carries six Raptors—three optimized for sea level and three designed for vacuum.

The engine cluster alone represents one of the biggest control challenges in aerospace history.

Super Heavy: A Booster Designed to Be Caught, Not Landed

Super Heavy’s job is simple in theory: lift Starship off the ground. In practice, it is an engineering monster.

After separation, Super Heavy flips around, fires its engines to slow down, and re-enters the atmosphere. Instead of landing on legs like Falcon 9, future versions are designed to be caught mid-air by the launch tower.

This eliminates the need for landing legs, saving mass and complexity. It also allows the booster to be placed directly back on the launch mount, ready for another flight.

Catching a rocket sounds insane—and it is—but it aligns perfectly with SpaceX’s obsession with rapid reuse.

Starship’s Wild Re-Entry and Belly-Flop Maneuver

Starship does not return to Earth like a capsule or a space shuttle. Instead, it falls through the atmosphere sideways, presenting its broad belly to the airflow.

This “belly-flop” maneuver dramatically increases drag, slowing the vehicle while spreading heat across its surface. Instead of wings, Starship uses four large flaps to control its orientation and descent.

Just before hitting the ground, Starship performs one of the most dramatic maneuvers in aerospace history. It reignites its engines, flips upright, and lands vertically in the final seconds.

This approach looks terrifying—but it eliminates wings, reduces structural mass, and makes the entire vehicle simpler and more robust.

The Heat Shield That Makes It All Possible

Starship’s heat shield consists of thousands of hexagonal ceramic tiles attached mechanically to the steel skin. Unlike the Space Shuttle, these tiles are designed to be easily replaceable and tolerant of minor damage.

Because the underlying structure is stainless steel, Starship can survive brief exposure even if some tiles are lost. This dramatically improves safety and reduces maintenance time.

The heat shield is one of the last major hurdles to full reusability—and one SpaceX continues to refine with every flight.

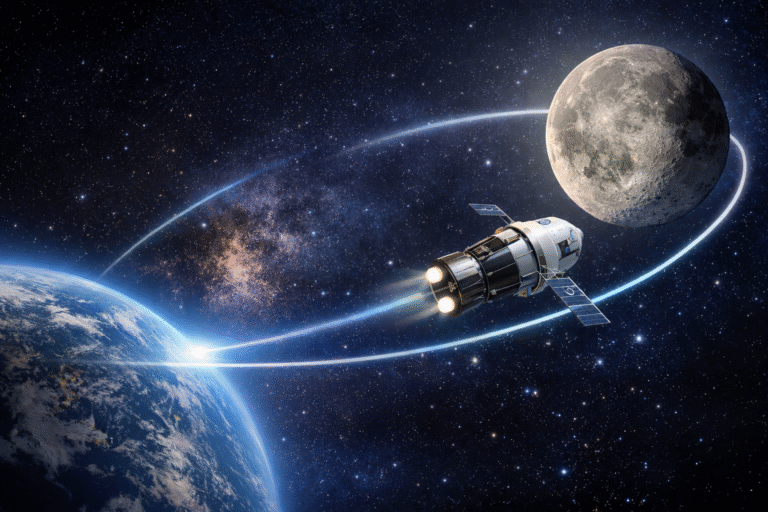

Designed for the Moon, Mars, and Beyond

Starship is not optimized for Earth orbit. It is optimized for planetary travel.

NASA’s lunar version removes heat shields and flaps entirely, replacing them with high-mounted landing thrusters designed to avoid kicking up lunar dust. For Mars, Starship’s size allows it to carry habitats, vehicles, power systems, and eventually people—all in a single launch.

No previous spacecraft has been designed with this level of flexibility from the beginning.

Why Starship Looks Chaotic — and Why That’s the Point

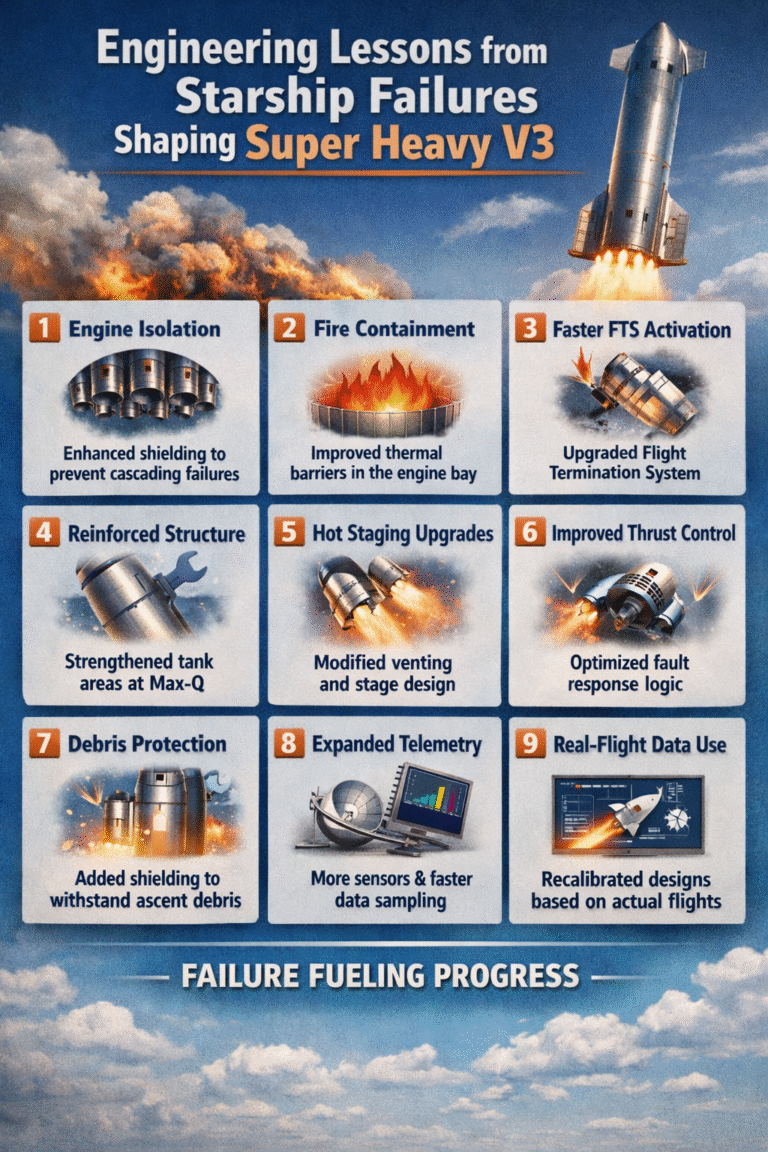

To outsiders, Starship development can look messy. Prototypes explode. Designs change rapidly. Vehicles are scrapped and rebuilt.

But this is not disorder—it is high-speed iteration.

SpaceX is learning by flying real hardware, gathering real data, and improving rapidly. This approach is risky, but it is also the only way to solve problems of this scale within a reasonable time.

Final Thoughts: Starship Is a Bet on the Future

Starship may fail. It may take longer than expected. It may require design changes we haven’t imagined yet.

But if it succeeds, it will do something no rocket ever has: make space travel ordinary.

That is why Starship matters—not because it is shiny or big, but because it is designed to change what humanity can realistically attempt beyond Earth.

And that is why this stainless-steel rocket, built in the open, may one day carry our species to another planet.