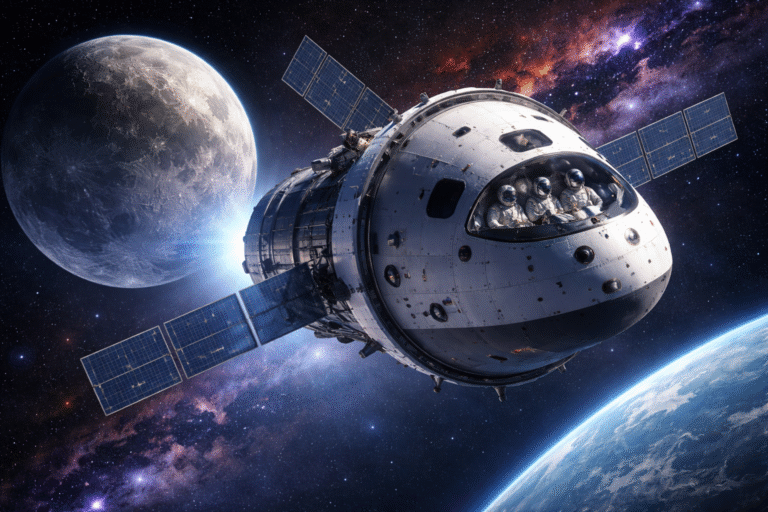

When NASA launched Artemis I in November 2022, it marked a triumphant return to deep-space exploration. An uncrewed Orion spacecraft circled the Moon, traveled farther than any human-rated spacecraft ever had, and returned safely to Earth after a 25.5-day mission. The flight validated the most powerful rocket ever built by NASA — the Space Launch System (SLS) — and demonstrated that Orion could survive the brutal conditions of deep space and high-speed atmospheric reentry.

But Artemis II is a completely different beast.

Scheduled for launch no earlier than 2026, Artemis II will carry four astronauts on a lunar flyby — the first humans to leave low Earth orbit since Apollo 17 in 1972. While Artemis I was a test of hardware, Artemis II is a test of human survival, system reliability, and NASA’s ability to manage risk at the edge of technological limits.

And make no mistake: Artemis II is far riskier than Artemis I, not because NASA is reckless, but because the mission crosses a threshold that multiplies complexity, consequence, and uncertainty.

1. Uncrewed vs Crewed: Why Human Spaceflight Changes Everything

The single biggest difference between Artemis I and Artemis II is the presence of humans.

Artemis I carried:

- No astronauts

- No active life support

- No medical contingencies

- No psychological stress factors

If something went wrong, engineers could observe, learn, and move on.

Artemis II, however, will carry:

- 4 astronauts

- Fully operational life-support systems

- Radiation exposure risks

- Limited abort options

- Real consequences for failure

Once Orion leaves Earth orbit, the crew will be hundreds of thousands of kilometers away, far beyond any rescue capability. Unlike the International Space Station — orbiting just 400 km above Earth — Artemis II astronauts cannot rely on rapid evacuation or resupply.

This alone elevates mission risk by an order of magnitude.

2. The Orion Heat Shield: A Known Issue, Not a Solved One

One of the most serious risk factors for Artemis II emerged because Artemis I succeeded.

During Artemis I’s return, Orion slammed into Earth’s atmosphere at nearly 40,000 km/h (25,000 mph) — faster than any spacecraft returning from low Earth orbit. Temperatures on the heat shield exceeded 2,760°C (5,000°F).

Although Orion landed safely, NASA later revealed something unexpected:

- The Avcoat heat shield material eroded unevenly

- Charred fragments broke away earlier than predicted

- Thermal performance differed from computer models

For an uncrewed mission, this was acceptable data.

For a crewed mission, it is a warning.

NASA chose not to redesign the heat shield for Artemis II, citing schedule and risk trade-offs. Instead, engineers plan to:

- Modify the reentry trajectory

- Avoid flight conditions that triggered abnormal erosion

- Reduce thermal stress duration

This approach lowers risk — but does not eliminate uncertainty.

In other words, Artemis II will fly with a heat shield that has shown unexpected behavior under real lunar-return conditions. That fact alone places Artemis II firmly in the “higher risk” category.

3. Life Support Systems: From Passive Hardware to Active Survival

Artemis I did not need:

- Oxygen generation

- Carbon dioxide removal

- Cabin pressure regulation

- Temperature and humidity control

- Waste management

- Emergency medical systems

Artemis II needs all of them, functioning flawlessly for over 10 days.

Orion’s Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS) has never been tested with humans beyond Earth orbit. Every breath the astronauts take depends on pumps, valves, sensors, and software behaving exactly as designed — in microgravity, radiation, and thermal extremes.

A minor malfunction on the ISS can be fixed with spare parts or crew assistance.

A similar malfunction halfway to the Moon becomes a mission-critical emergency.

NASA’s own risk models acknowledge that:

- Medical emergencies in deep space are rare but not negligible

- Crew autonomy must replace real-time Earth intervention

- Decision-making delays increase with distance

This is not theoretical risk — it is operational reality.

4. Radiation Exposure: Beyond Earth’s Protective Shield

Low Earth orbit is protected by Earth’s magnetosphere, which shields astronauts from most cosmic radiation. The Moon is not.

During Artemis II, astronauts will:

- Spend days outside the magnetosphere

- Be exposed to galactic cosmic rays

- Face potential solar particle events (SPEs)

While the mission duration is short compared to Mars missions, radiation exposure is still significant. A major solar flare during transit could deliver doses approaching or exceeding recommended limits — and there is no way to “hide” in deep space.

Artemis I did not care about radiation.

Artemis II must manage it carefully.

5. Communication Risks: Humans Need More Than Telemetry

Uncrewed missions can tolerate:

- Brief signal loss

- Delayed telemetry

- Partial data gaps

Crewed missions cannot.

Artemis II depends on NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) — a global array of massive antennas in California, Spain, and Australia. Any degradation in DSN availability increases risk during:

- Trajectory corrections

- System troubleshooting

- Emergency decision-making

In recent years, parts of the DSN infrastructure have faced maintenance challenges, highlighting the fragility of the communication backbone supporting human deep-space exploration.

For Artemis II, communication isn’t just about data — it’s about crew confidence, coordination, and survival.

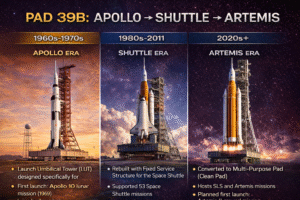

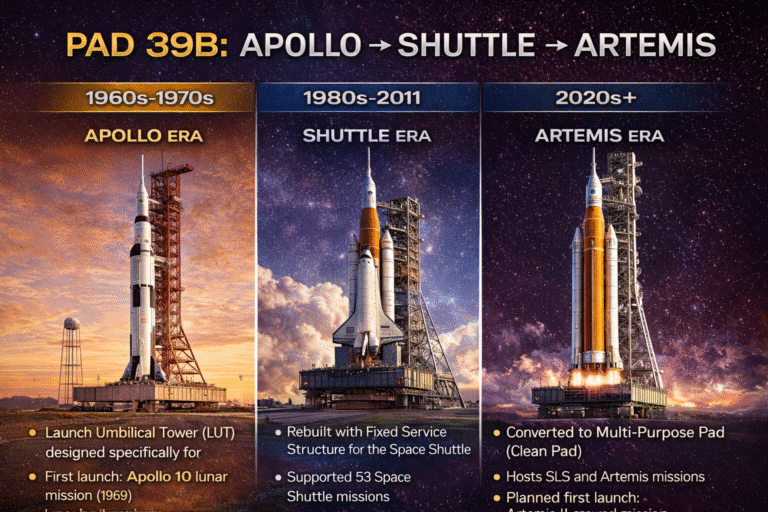

6. SLS Rocket: One Flight Is Not a Track Record

The Space Launch System flew once — on Artemis I.

Yes, it worked.

But in aerospace, one successful flight does not equal maturity.

Artemis II introduces:

- Human-rating requirements

- Modified flight profiles

- Adjusted booster separation dynamics

- New vibration and acoustic constraints

The SLS core stage burns over 2 million liters of liquid hydrogen and oxygen in about 8 minutes. Any anomaly during ascent leaves minimal time for crew escape decisions.

While Orion has a launch abort system, escape at SLS scale has never been tested with humans aboard.

This is not fear-mongering — it is statistical reality.

7. Human Factors: Stress, Fatigue, and Isolation

Astronauts are highly trained, but they are still human.

Artemis II astronauts will face:

- Isolation far beyond Earth orbit

- No immediate rescue option

- Constant awareness of mission risk

- Long periods of confined living space

Psychological stress compounds technical risk. Fatigue affects decision-making. Small errors can cascade into larger problems.

Apollo missions faced similar pressures — but Artemis II operates within a far more complex technological environment, where software, automation, and human oversight must coexist seamlessly.

8. Schedule Pressure and Political Reality

Artemis is not just a space program — it is a geopolitical and budgetary project.

The Artemis program has already cost over $90 billion, and every delay increases scrutiny from:

- U.S. Congress

- International partners

- Competing space programs

Artemis II’s timeline has slipped multiple times, creating pressure to proceed once minimum safety thresholds are met — not necessarily when all unknowns are eliminated.

History shows that schedule pressure is one of the most dangerous forces in aerospace decision-making.

9. Why Artemis II Still Matters Despite the Risk

Risk does not mean recklessness.

Artemis II is essential because:

- It validates human deep-space flight

- It tests systems before lunar landing missions

- It restores human presence beyond Earth orbit

- It lays groundwork for Mars exploration

Without Artemis II, Artemis III — a crewed lunar landing — cannot happen.

Progress in space has always required risk, from Mercury to Apollo to Shuttle to Artemis.

Final Verdict: Why Artemis II Is Objectively Riskier

Artemis II is riskier than Artemis I because it introduces:

- Human lives

- Active life support

- Radiation exposure

- Psychological factors

- Narrower margins for error

- Fewer recovery options

Artemis I tested hardware.

Artemis II tests human survival in deep space.

And that is precisely why the mission matters.

If Artemis II succeeds, it will prove that humanity is ready — once again — to venture beyond Earth, not just with machines, but with people.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Artemis II?

Artemis II is NASA’s first crewed mission under the Artemis program. It will send four astronauts on a lunar flyby, carrying them beyond low Earth orbit for the first time since the Apollo missions more than 50 years ago.

How is Artemis II different from Artemis I?

Artemis I was an uncrewed test flight designed to validate the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and the Orion spacecraft. Artemis II builds on that mission but adds human astronauts, fully active life-support systems, and crew safety requirements—making it far more complex and risky.

Why is Artemis II considered more dangerous than Artemis I?

Artemis II introduces real human risk. Unlike Artemis I, the mission must rely on life-support systems that have never been used by astronauts in deep space, manage radiation exposure beyond Earth’s magnetosphere, and return through Earth’s atmosphere using a heat shield that showed unexpected behavior during Artemis I.

What issue was found with Orion’s heat shield during Artemis I?

During Artemis I’s high-speed lunar return, NASA observed that parts of Orion’s heat shield eroded differently than predicted. Although the spacecraft landed safely, the findings raised concerns that required trajectory adjustments for Artemis II to reduce thermal stress during reentry.

Will NASA redesign the heat shield for Artemis II?

No. NASA decided not to redesign the heat shield for Artemis II due to schedule and risk trade-offs. Instead, engineers will modify the spacecraft’s reentry profile to avoid the conditions that caused unexpected material erosion during Artemis I.

How far will Artemis II astronauts travel from Earth?

Artemis II astronauts will travel roughly 400,000 kilometers (about 250,000 miles) from Earth, taking them farther than any human has traveled since Apollo 17 in 1972.

How long will the Artemis II mission last?

The Artemis II mission is expected to last around 10 days, including launch, lunar flyby, and return to Earth.

What radiation risks do Artemis II astronauts face?

Once beyond Earth’s magnetic field, astronauts will be exposed to higher levels of cosmic radiation and potential solar particle events. While the mission is relatively short, radiation exposure is still a significant concern compared to missions in low Earth orbit.

Can astronauts abort the mission if something goes wrong?

Abort options are limited once Orion leaves Earth orbit. While the spacecraft has emergency capabilities, Artemis II astronauts cannot return immediately or receive rescue assistance like crews aboard the International Space Station.

Why is Artemis II still necessary despite the risks?

Artemis II is essential to proving that humans can safely travel beyond Earth orbit using modern spacecraft. Its success is critical before NASA attempts Artemis III, which aims to land astronauts on the Moon’s south pole.

When is Artemis II expected to launch?

As of current planning, NASA is targeting no earlier than 2026, though exact launch dates depend on technical readiness and mission reviews.

Why is Artemis II important for future Moon and Mars missions?

Artemis II will validate human deep-space flight systems needed for long-term lunar exploration and future crewed missions to Mars. It serves as the bridge between testing hardware and establishing a sustained human presence beyond Earth.