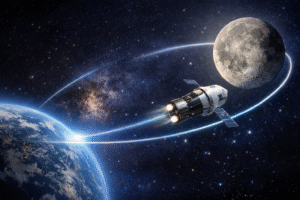

The Artemis II mission represents a monumental leap in human spaceflight — the first time astronauts will travel beyond low Earth orbit in more than five decades. A core part of this historic voyage is the free-return trajectory, a precisely calculated path that allows the Orion spacecraft to reach the Moon and return safely to Earth using the natural gravity of the Earth–Moon system. In this comprehensive explainer, we’ll unpack what the free-return trajectory is, why NASA uses it, the physics behind it, key mission facts and numbers, and how this trajectory ensures astronaut safety. We’ll also link back to your pillar article to amplify engagement and search engine ranking.

🌕 What Is a Free-Return Trajectory?

A free-return trajectory is an orbital path that takes a spacecraft from Earth to the vicinity of the Moon and then back to Earth without the need for major propulsion burns on the return leg. Instead, the gravity of the Moon and Earth work together like a celestial slingshot to bend and redirect the spacecraft’s path.

In essence, a free-return trajectory is a safety-first flight path — if something goes wrong after translunar injection, the spacecraft will still naturally loop back to Earth without needing major engine maneuvers. This design was first used successfully during the early Apollo missions in the 1960s and was central to the safe return of Apollo 13’s crew when their service module was damaged. (Wikipedia)

🚀 Artemis II Mission — Quick Overview

Before we dive into the mechanics of the free-return path, it helps to quickly recap the Artemis II mission:

- Mission: Artemis II — first crewed flight of NASA’s Artemis program

- Launch Vehicle: Space Launch System (SLS) Block 1

- Crew: 4 astronauts — Reid Wiseman (Commander), Victor Glover (Pilot), Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen (Canadian Space Agency) (NASA)

- Duration: ~10 days

- Objective: Fly around the Moon and return to Earth without landing

- Trajectory: Free-Return (hybrid free-return that returns crew to Earth) (NASA)

- Historical Context: First human journey beyond low Earth orbit since Apollo 17 in 1972. (Wikipedia)

The mission’s real value lies in validating life-support systems, deep space navigation, radiation protection, communications, and more — all essential checks before crews return to the lunar surface on Artemis III. (NASA)

👉 For a full timeline, crew info, risks, countdown, and live launch updates, explore your detailed resource: Artemis II Launch Live Updates, Countdown, Crew, Risks & Timeline

📌 Why NASA Uses a Free-Return Trajectory

1. Safety First

The free-return path inherently guides the spacecraft back to Earth if major propulsion fails after translunar injection (TLI). This is vital for the first crewed deep space mission, minimizing reliance on engines for a safe return.

2. Fuel Efficiency

Using gravity to bend the spacecraft’s path reduces the delta-V (change in velocity) needed for the return trip. That means the spacecraft doesn’t carry as much fuel, which reduces weight and complexity.

3. Proven Track Record

Free-return trajectories were key to early Apollo missions and provided a fail-safe for Apollo 13, where a critical system failure forced the crew to rely on gravitational forces for return. (Wikipedia)

4. Optimal for Testing Systems

Since Artemis II doesn’t enter lunar orbit or land, a free-return trajectory is perfect for testing Orion’s life-support, navigation, and communications systems over long distances.

📐 How the Free-Return Path Works — Step by Step

To understand Artemis II’s free-return trajectory, we need to break the mission down into key phases:

1. Launch & Earth Orbit

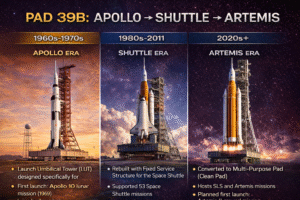

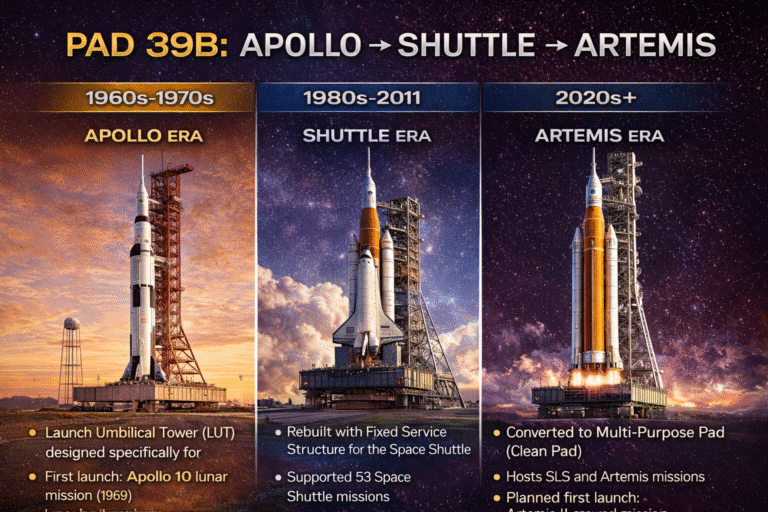

After liftoff from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Pad 39B aboard the SLS Block 1 rocket, the Orion crew module and upper stage enter low Earth orbit. The initial orbit is elliptical, roughly 115 miles × 1,800 miles, lasting about 90 minutes. (NASA)

2. High Earth Orbit

A second burn of the upper stage sends Orion into a much higher Earth orbit — approximately 235 miles × 68,000 miles. This orbit allows the spacecraft to build up the speed needed for translunar injection. (NASA)

3. Translunar Injection (TLI)

Once in the high orbit, Orion’s service module fires its engine for the translunar injection burn, propelling the spacecraft out of Earth’s gravity well toward the Moon. This burn sets Orion on the free-return path.

4. Lunar Flyby

During the outbound journey of about 4 days, Orion will travel to the far side of the Moon. At its closest point, it could be between 4,000–6,000 miles above the lunar surface, depending on launch timing. (NASA)

This is also when communications blackout occurs — the spacecraft is behind the Moon, out of direct line-of-sight with Earth. (NASA)

5. Gravity Slingshot

As Orion passes behind the Moon, lunar gravity subtly alters its trajectory — bending it toward Earth. This gravity assist is what makes the free-return path “free” of major propulsion burns.

6. Return to Earth

Without additional major burns, Earth’s gravity naturally draws Orion back. Orion re-enters the atmosphere at roughly 25,000 mph, deploying drogue and main parachutes to slow down and splash down in the Pacific Ocean. (NASA)

📊 Key Numbers & Mission Facts

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Mission Duration | ~10 days |

| Total Round-Trip Distance | >620,000 miles |

| Maximum Distance from Earth | ~230,000–240,000 miles |

| Closest Approach to Moon | ~4,000–6,000 miles |

| Re-entry Speed | ~25,000 mph |

| Drop Zones for Splashdown | Pacific Ocean |

| Number of Astronauts | 4 (3 Americans, 1 Canadian) |

| First Crewed Beyond Low Earth Orbit | Since Apollo 17 (1972) |

All figures reference NASA mission profiles and official planning documents. (NASA)

🧠 The Physics Behind Free-Return Trajectories

The key to understanding free-return trajectories is gravitational dynamics — how the combined gravity of two massive bodies (Earth and Moon) influences an object’s motion.

Gravity Slingshot

As Orion approaches the Moon, the Moon’s gravity pulls on the spacecraft. This interaction changes the spacecraft’s velocity vector without the spacecraft expending additional fuel. Essentially:

- Before lunar encounter: spacecraft moving outward from Earth

- During flyby: lunar gravity curves the path

- After flyby: spacecraft now on path back toward Earth

The technique uses principles of orbital mechanics, and variations of these trajectories have been used on lunar and interplanetary missions since the 1960s. (Wikipedia)

Why It’s Called “Free Return”

The term “free” doesn’t mean without any course corrections — Orion will still perform small trajectory correction burns — but it does mean that the core return path doesn’t require main engine burns. Instead, gravity does the work.

🔒 Safety and Mission Assurance

Safety is at the heart of Artemis II’s design, and the free-return trajectory plays a central role.

Abort Options & Contingencies

NASA engineers design multiple abort modes in deep space, allowing Orion to alter course if needed. But the free-return trajectory offers a baseline fallback — even if major propulsion systems fail after TLI.

Redundancy

Orion’s navigation, guidance, life-support, radiation monitoring, and communications systems are all thoroughly tested throughout the mission. This ensures redundancies are in place for key phases, including lunar flyby and Earth re-entry.

Historical Precedent

Unlike Artemis I — the uncrewed precursor mission — Artemis II carries astronauts, which means mission planners prioritize paths that provide contingency for returning with minimal dependence on spacecraft engines. (NASA)

📈 Why This Matters for Artemis III and Beyond

Artemis II isn’t just a stunning engineering achievement; it’s a critical stepping stone to returning humans to the lunar surface and eventually sending crew to Mars.

- Verifying Systems: Orion’s performance with humans aboard is essential before lunar landing missions.

- Data Collection: Radiation exposure data, communication performance, and navigation accuracy all feed into planning for Artemis III and later missions.

- Public Confidence: Success reinforces NASA’s Artemis program roadmap and supports global and commercial partnerships.

📌 Common Misconceptions About Free-Return Trajectories

“They Don’t Need Engines at All”

While the core return path doesn’t require a major engine burn, small trajectory correction burns are still used to keep the spacecraft on target and compensate for tiny deviations.

“It’s a Full Moon Orbit”

Artemis II does not enter lunar orbit. Instead, it executes a flyby — looping around the far side of the Moon before returning to Earth. (NASA)

📌 Final Thoughts

The free-return trajectory is one of the most elegant applications of orbital mechanics in human spaceflight. It leverages gravity itself as a guiding force — reducing fuel needs, enhancing safety, and honoring a legacy of lunar exploration that began with Apollo missions.

As Artemis II prepares for its launch window in early 2026, this trajectory stands not just as a flight path, but as a symbol of NASA’s commitment to safe, sustainable exploration of the Moon and beyond.

👉 For detailed timelines, crew profiles, countdown info, and live mission updates, be sure to read your pillar article on Artemis II’s launch and mission plan: https://chimniii.com/artemis-ii-launch-live-updates-countdown-crew-risks-timeline/