Did you know that a rocket is most likely to fail not at liftoff, but nearly 80 kilometers above Earth, when invisible forces try to tear it apart?

That critical moment is called Max-Q, and precise engine throttling during Max-Q is what separates a successful space mission from a catastrophic failure. For just a few seconds, rockets face the highest aerodynamic stress of their entire journey—and there is zero margin for error.

What Is Max-Q and Why Does It Occur Around 80 km?

Max-Q refers to the point of maximum dynamic pressure experienced by a rocket during ascent. As the vehicle accelerates rapidly while still moving through Earth’s atmosphere, the combination of increasing velocity and remaining air density creates extreme aerodynamic forces.

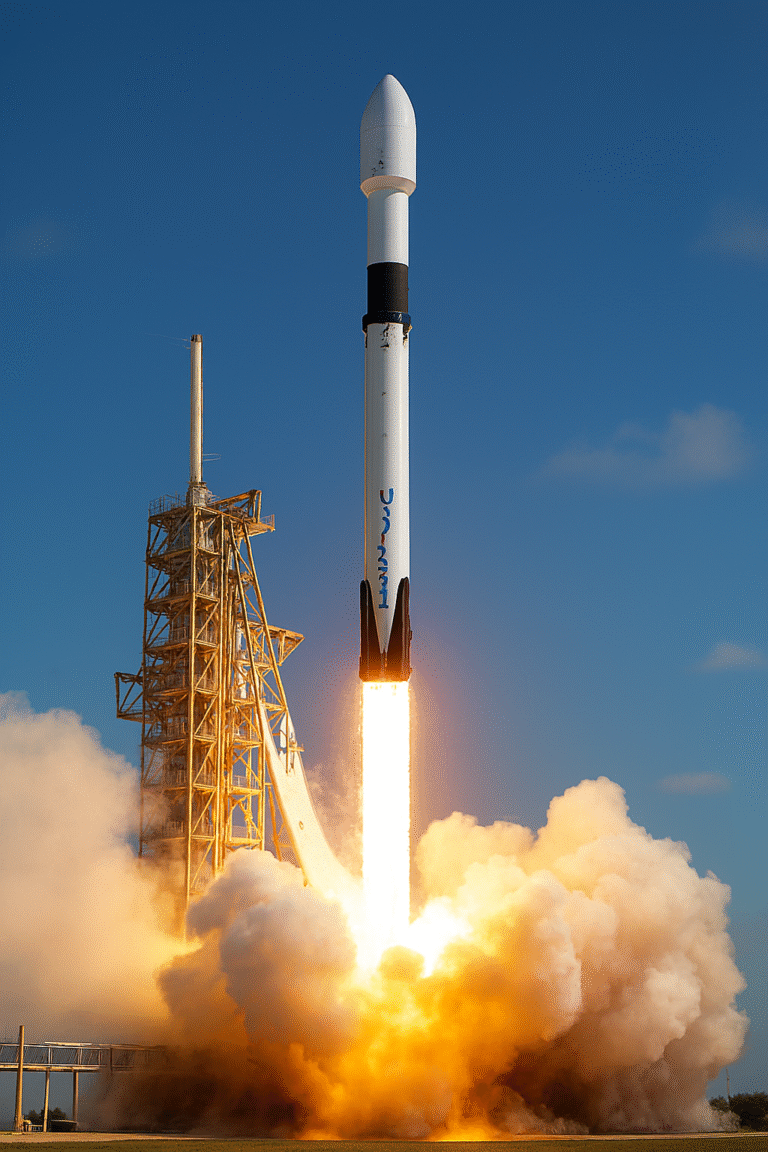

For most modern rockets, including SpaceX Falcon 9, Starship, NASA’s SLS, and ISRO’s LVM3, Max-Q typically occurs between 70 and 85 kilometers altitude. At this stage, even minor structural weakness or control error can escalate into a mission-ending event.

According to NASA, Max-Q is one of the most structurally demanding phases of flight, requiring exact control of thrust and trajectory to avoid failure (https://www.nasa.gov).

Why Precise Engine Throttling During Max-Q Is Absolutely Critical

During Max-Q, engines are deliberately throttled down—sometimes by as much as 30–40 percent. This is done to limit acceleration and reduce aerodynamic loads acting on the rocket’s structure.

Precise engine throttling during Max-Q is critical because thrust directly controls how much force the vehicle experiences. Too much thrust increases stress on the rocket’s skin, tanks, and internal load paths. Too little thrust can destabilize the ascent profile and compromise orbital insertion.

SpaceX regularly highlights this moment during live launches, announcing “Throttle down for Max-Q” before gradually ramping engines back up once the danger passes (https://www.spacex.com).

What Happens If Engine Throttling Goes Wrong at Max-Q?

When precise engine throttling during Max-Q fails, consequences can be severe and immediate.

If engines do not throttle down enough, aerodynamic pressure may exceed design limits. This can lead to structural deformation, tank rupture, or complete vehicle breakup. Early rocket programs experienced multiple failures before engineers fully understood Max-Q dynamics.

On the other hand, excessive or mistimed throttling can cause guidance instability, wasted fuel, or failure to achieve orbital velocity. In crewed missions, such deviations can trigger abort systems, placing astronauts at risk.

NASA investigations have repeatedly shown that rockets experience their highest combined stress loads during Max-Q, making precision control non-negotiable.

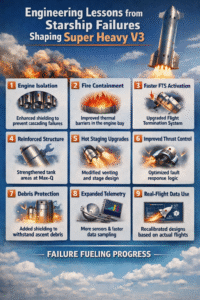

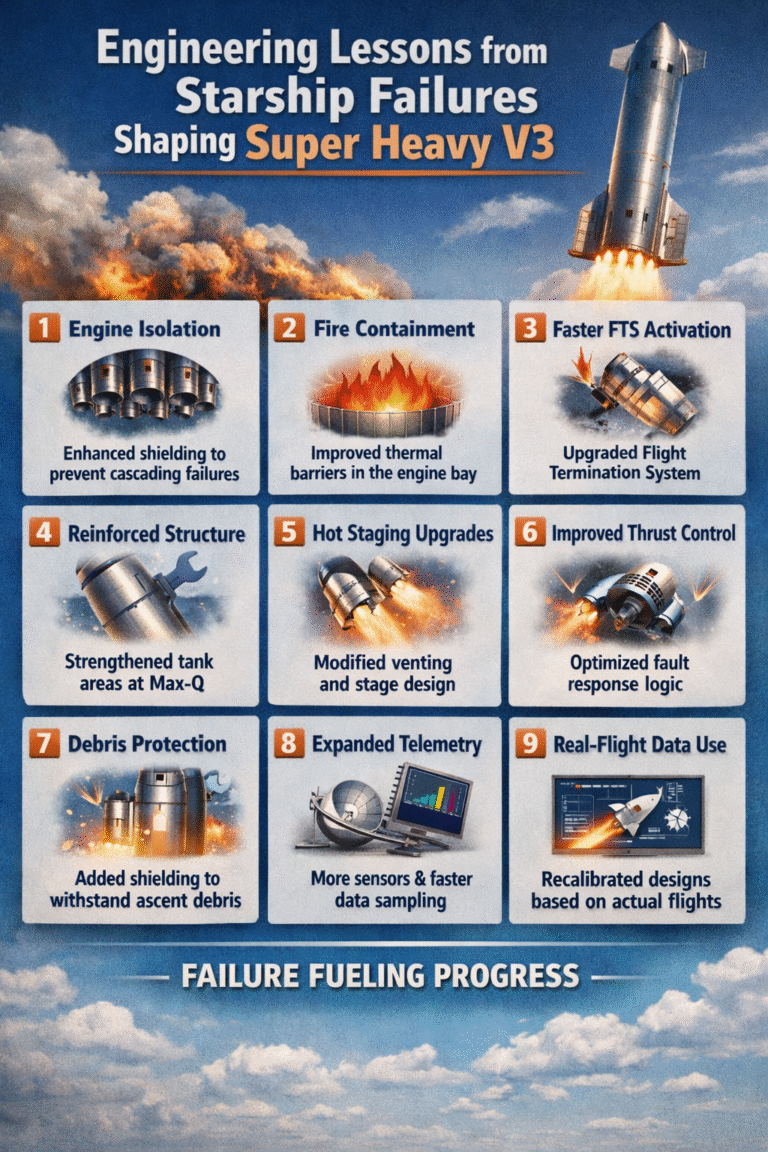

Why Max-Q Is Even More Dangerous for Modern Reusable Rockets

Reusable rockets face a tougher challenge. Vehicles like Falcon 9 boosters and SpaceX Starship must survive Max-Q repeatedly, not just once.

Each flight subjects the structure to cyclic loads, vibration, and thermal stress. Engineers rely on real-time sensor data, adaptive guidance systems, and refined throttling curves to maintain safety margins.

Elon Musk has described ascent loads—including precise engine throttling during Max-Q—as one of the hardest engineering problems SpaceX continues to refine (https://www.teslarati.com).

Why This Matters Beyond Rocket Science

You may never board a spacecraft, but your daily life depends on rockets surviving Max-Q.

Satellites powering GPS navigation, mobile networks, weather forecasting, television broadcasting, and internet infrastructure all depend on flawless launches. A single Max-Q failure can delay missions worth billions of dollars and disrupt global services.

For India, mastering precise engine throttling during Max-Q is essential for the success of ISRO’s Gaganyaan human spaceflight program, where astronaut safety is paramount (https://www.isro.gov.in).

The Most Dangerous Seconds You’ll Never See

Max-Q lasts only a few seconds—but those seconds decide everything.

If throttling is precise, the rocket clears the pressure wall and accelerates safely into thinner atmosphere. If not, forces multiply faster than software or humans can react.

There is no reset button in spaceflight.

That’s why engineers quietly consider Max-Q the most dangerous moment of every launch.

Final Thoughts: Why Max-Q Deserves Public Attention

Next time you watch a rocket launch, don’t blink when commentators mention Max-Q. That announcement marks the moment when physics is at its most unforgiving—and engineering precision must be flawless.

If you found this article insightful, share it, comment your thoughts, and follow our page for deeper explanations of the hidden science behind space exploration 🚀

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does Max-Q mean in rocket launches?

Max-Q is the point of maximum aerodynamic pressure during ascent.

Why is precise engine throttling during Max-Q necessary?

It prevents structural overload while maintaining stable flight dynamics.

At what altitude does Max-Q usually occur?

Typically between 70 and 85 km, depending on vehicle and atmosphere.

Can a rocket fail if throttling is incorrect at Max-Q?

Yes. Incorrect throttling can cause structural failure or mission loss.

Is Max-Q dangerous for astronauts?

Absolutely. It is one of the most critical safety phases in human spaceflight.

Do reusable rockets face more Max-Q risk?

Yes, because they must survive repeated high-stress Max-Q events.