How SpaceX may refuel Starships in space

SpaceX should be able to transfer 1000+ tonnes of fuel in a few hours with massive pipes linking each Starship's tanks. Ultimately, even at Starship's magnitude, settled propellant transfer should cost no more than 20-50 tonnes of propellant every refuelling. Since 2019, SpaceX Dragon spacecraft have successfully independently docked with the International Space Station 27 times in nine years. SpaceX has effectively already cleared the last remaining technological hurdle for settled propellant transfer and should be able to quickly refuel Starships in orbit with little to no substantial development required. Aside from the obvious (preparing a new rocket for flight tests), SpaceX's only major refuelling issue is the umbilical ports and docking procedures.

Equation of REUSE/REFUEL

Mastery of reusability and orbital refuelling are mutually included in SpaceX's aspirations to expand humankind to Mars. Neither alone will allow for a sustained Mars metropolis. Not being able to quickly and efficiently refuel in space means that a Starship launch system can't affordably build, supply, and inhabit a city on another planet (or Moon).

This might allow for limited interplanetary travel and the establishment of a small human base on Mars, but it would be much more complex, risky, and expensive to operate and would require a large fleet of ships and rockets from the start.

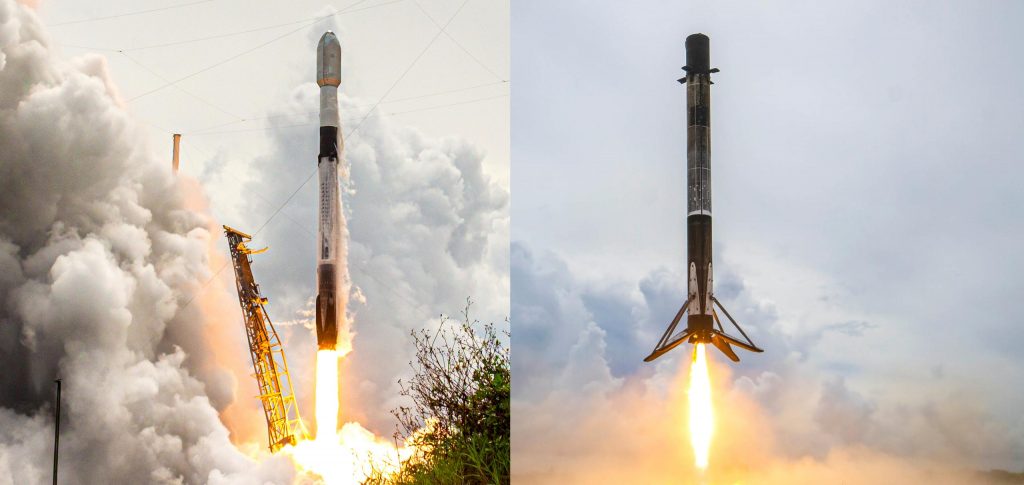

The question of how SpaceX can make Starship the world's fastest, most reliable, and cheapest reusable rocket is tough to answer, but not impossible. The current Falcon booster turnaround record is two launches in less than four weeks (27 days).

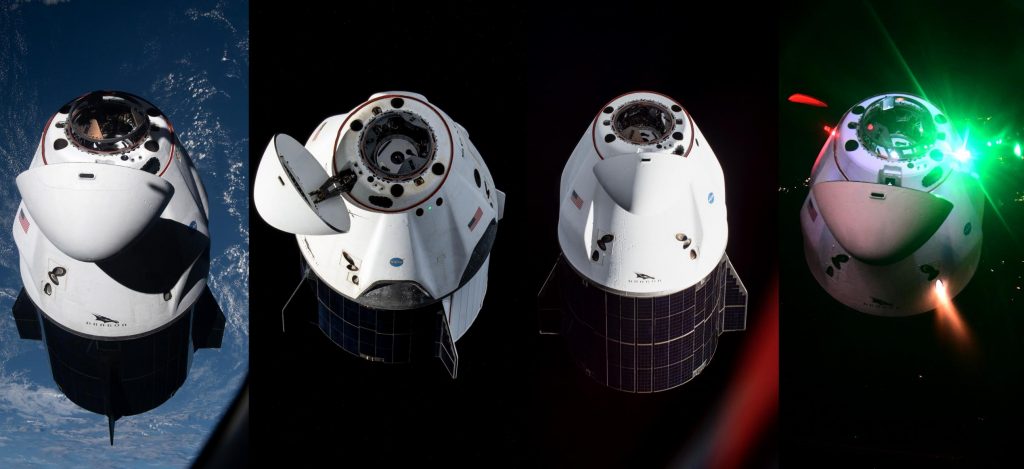

SpaceX recently flew the same orbital Crew Dragon capsule twice in just 137 days (less than five months) – swiftly nearing NASA's Space Shuttle typical turnaround times.

Advertisement

The current fleet of four reusable Dragon spacecraft operated by SpaceX. (NASA/Mike Hopkins/ESA/Thomas Pesquet)

Falcon 9 B1060, pictured here during its most recent launch, holds SpaceX's record for fastest turnaround time of just 27 days and has conducted eight orbital-class launches in 12 months, averaging one flight every 45 days — a turnaround rate faster than the Space Shuttle's all-time record. (Credit: SpaceX)

However, Dragon is only partially reusable and requires extensive refurbishing after recovery, and Falcon 9 boosters are quite complex. As a result, Starship should be significantly more complex but potentially far more reusable than Falcon upper stage. No deployable legs or fins; no structural composite-metal joints; no dedicated manoeuvring thrusters; and its clean-burning Raptor engines should be easier to utilise than Falcon's Merlins. SpaceX can answer the reusability portion of the equation based on precedents set by Falcon rockets and NASA's Space Shuttle.

Advertisement

HOW ABOUT REFUELING?

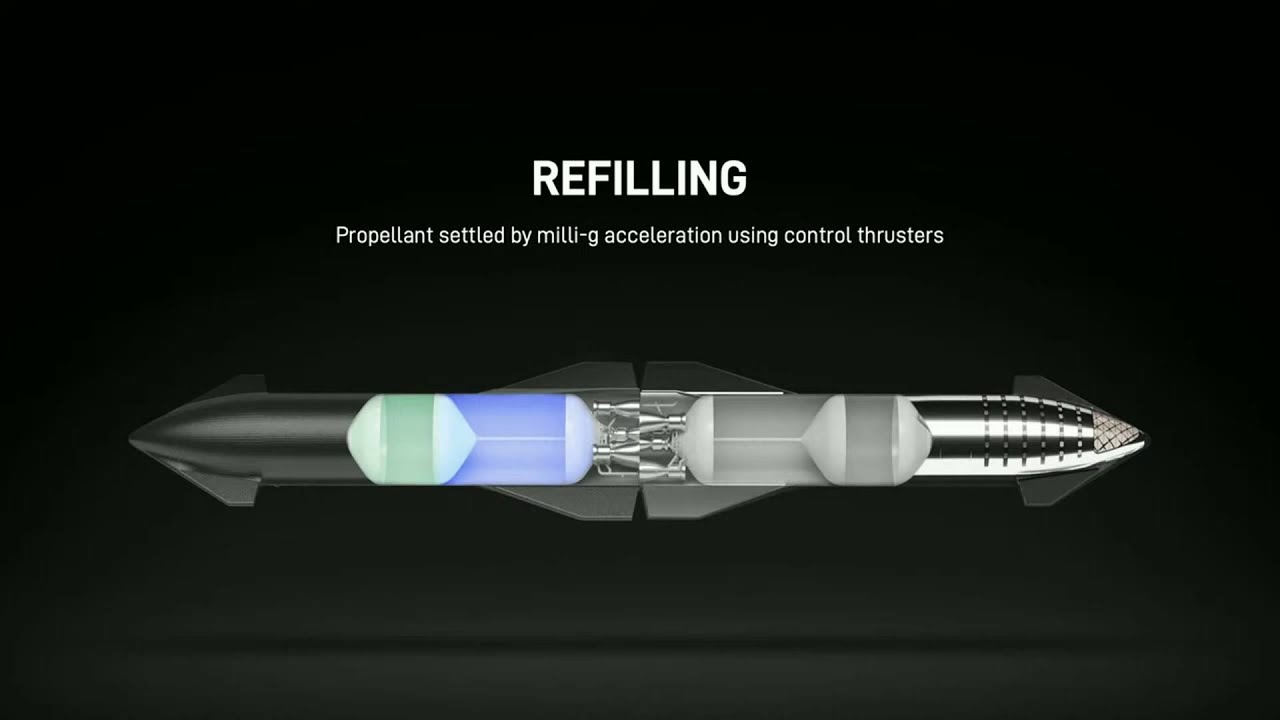

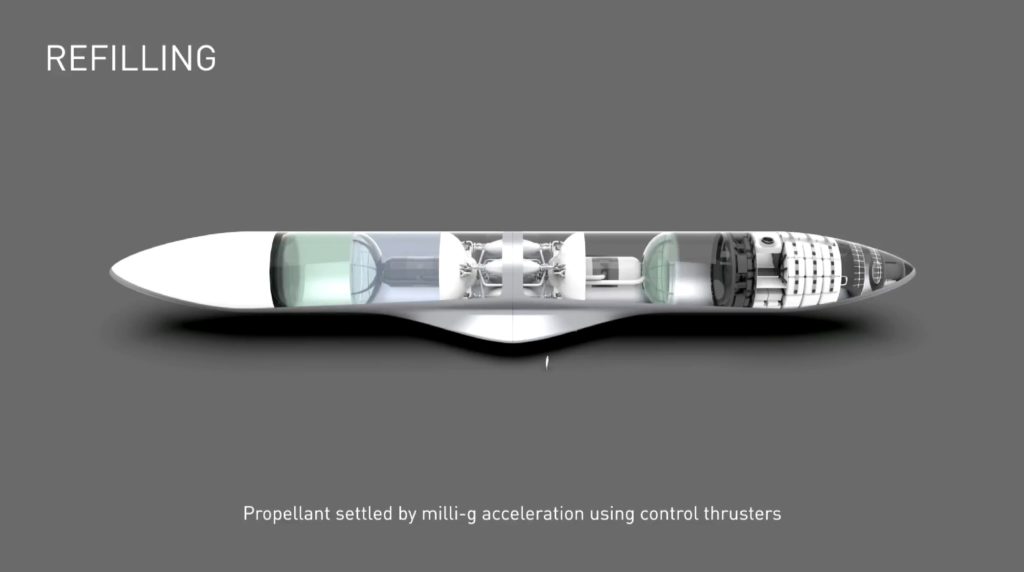

But the other side of the equation is quite different. “Propellant settled via milli G acceleration employing control thrusters” sums up SpaceX's official discussions about orbital refuelling.

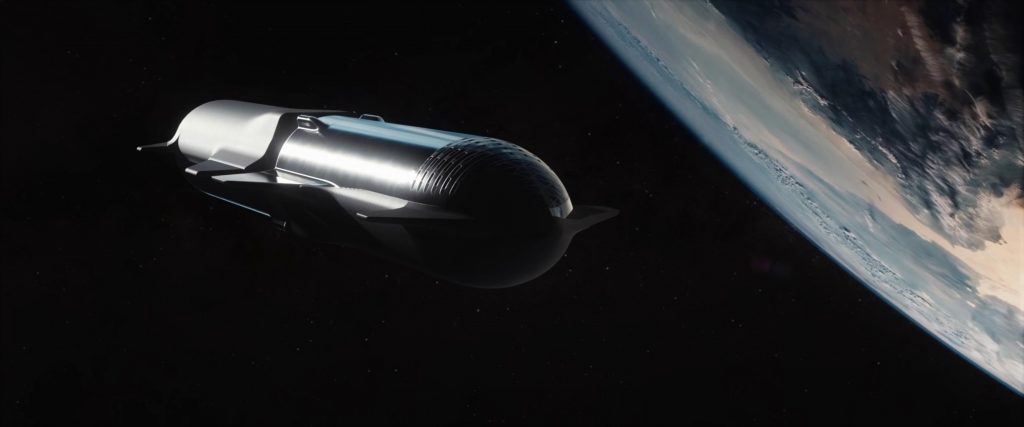

Credit: SpaceX

On the surface, that little phrase doesn't say much. With a few grains of salt, hints from the company's CEO's past statements, and historical context, it's feasible to construct a reasonably complete picture of how SpaceX would likely refuel Starships in space. The cornerstone is a 2006 article titled “Settled Cryogenic Propellant Transfer” by seven Lockheed Martin employees and a NASA engineer. In addition to addressing the title's obvious implications, the study concentrates on the authors' preferred method of large-scale orbital propellant transfer.

In microgravity, propellant inside a spacecraft's tanks effectively detaches from the vehicle's construction. By Newton's first law of motion, a spacecraft's propellant will stay stationary until it splashes against its tank walls. If a spacecraft thrusts in one direction and opens a hatch or valve in the other direction, the propellant inside will naturally escape out of the opening. A tanker's propellant is effectively pushed into the receiving ship's propellant tanks when a ship in need of fuel docks with a tanker and their tanks are connected and opened.

This ‘settled propellant transfer' works on basic and intuitive principles. The key question is how much continuous acceleration is required and how much it costs. Using a 100 metric tonne ( 220,000 lb) spacecraft pair accelerating at 0.0001G (one ten-thousandth of Earth gravity) to transfer fuel would use only 45 kg (100 lb) of hydrogen and oxygen propellant each hour.

Advertisement

In Pic: Two possible propellant transfer orientations. (Credit: SpaceX)

With two docked Starships, the combined weight would be closer to 1600 tonnes (3.5 million pounds) and the “Milli G” acceleration SpaceX has often cited in presentation slides would be 10 times larger than the highest acceleration evaluated by Kutter et al. Nonetheless, their article claims that propellant cost increases linearly with desired acceleration and mass. A milli-G Starship would potentially require slightly over 7 tonnes (half a percent) of its methane and oxygen propellant every hour to maintain milli-G acceleration.

SpaceX should be able to transfer 1000+ tonnes of fuel in a few hours with massive pipes (20-50 cm or 8-20 in) linking each Starship's tanks. Ultimately, even at Starship's magnitude, settled propellant transfer should cost no more than 20-50 tonnes of propellant every refuelling. Prior to the 1600-ton scenario, all transfers should be significantly more efficient.

Overall, refuelling an orbiting Starship or depot with 1200 tonnes of propellant should be fairly efficient, with potentially 80% or more of the propellant launched remaining available at the end.

Advertisement

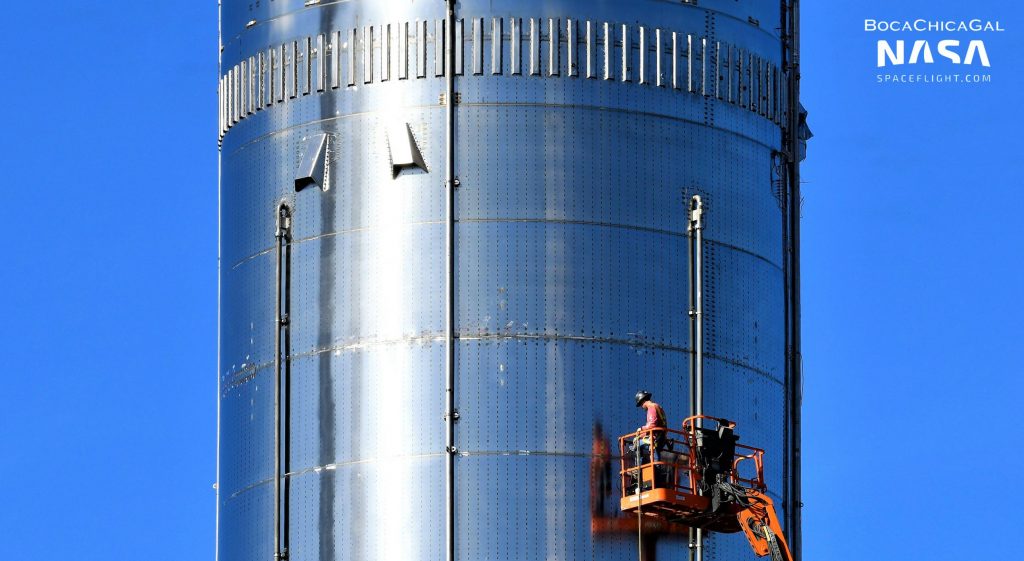

In Pic: SpaceX has fitted nozzles over Super Heavy B4's main oxygen tank vents to direct and maximise thrust. (Credit: NASASpaceflight)

A hypothetical spaceship may even use ullage gas vents to accomplish the requisite acceleration, negating the requirement for custom-designed settling thrusters, according to Kutter et al. On Starship's Super Heavy rocket, SpaceX (or CEO Elon Musk) has recently elected to deploy strategically situated ullage vents instead of purpose-built manoeuvring engines. As cryogenic propellant warms and spontaneously boils into gas, the combination of ullage vents employed to release the additional pressure may provide enough thrust to transport enormous volumes of propellant.

Finally, more than a decade ago, Kutter et al predicted that the main technological hurdle to large-scale settled propellant transfer would be the ability to autonomously rendezvous and dock in orbit. Contrary to Russian practise, the US had never proven autonomous docking and rendezvous technologies on its own Soyuz and Progress spacecraft in 2006. Since 2019, SpaceX Dragon spacecraft have successfully independently docked with the International Space Station 27 times in nine years.

Advertisement

In Pic: SpaceX already has hot-gas Raptor-derived moving thrusters that could be readily added to Starship to improve settled propellant transfer efficiency at the tradeoff of weight and complexity. (Credit: NASASpaceflight)

The path to refuelling (or refilling, as Musk prefers) Starships in orbit has been paved by decades of NASA and industry research. The evidence implies that SpaceX has taken the same course.

SpaceX has effectively already cleared the last remaining technological hurdle for settled propellant transfer and should be able to quickly refuel Starships in orbit with little to no substantial development required.

There is a risk that small to moderate issues will be discovered and addressed once SpaceX begins testing refuelling in orbit, but there are no clear roadblocks in the way of such tests. Aside from the obvious (preparing a new rocket for flight tests), SpaceX's only major refuelling issue is the umbilical ports and docking procedures.

These ports/mechanisms will need to be located and whether to use ullage vent ‘thrusters', cold gas thrusters like the Falcon and current Starship prototypes, or more efficient hot-gas thrusters like Raptors. In the end of the day, those are all solved challenges and SpaceX is an expert at sophisticated but routine systems engineering.

Advertisement