Atmanirbhar Bharat: A Dream Comes True for India in the Defence Sector

Friday, October 22, 2021 | Chimniii Desk

Key Points

The Indian Army consumes more than half of India's overall defence budget, with the majority of expenditure going into cantonment maintenance, pay, and pensions rather than crucial equipment and ammunition. Between 2016 and 2020, India became the second-largest importer of weaponry, accounting for 9.5% of worldwide imports. The new companies now have a Rs 65,000 crore order book. The Ministry of Defence has set a target of $25 billion (Rs 1.75 lakh crore) in defence manufacturing revenue by 2025, which includes a $5 billion (Rs 35,000 crore) export target for military gear. Despite these initiatives, India's military industry remains underdeveloped, and the private sector is still not considered a partner in the country's quest for greater self-reliance. Corporatization of the OFB must be viewed in the broader context of India's military industry capability, self-reliance quotient, design capability in critical systems and their quality, timeliness, and cost-effectiveness, as well as the involvement of private players in defence manufacturing as partners alongside OEMs and design houses.

Advertisement

Credit: Quint

Credit: QuintIts robust economy and robust military are indicators of a nation's strength. India, on the other hand, has a powerful economy but a weak army thus far. It is unclear that they will be able to endure coordinated operations by China and Pakistan, backed up by Taliban Afghanistan, without the full assistance of the US. India must consequently develop self-sufficiency – Atmanirbhar – in order to vanquish the adversary.

The Indian Army consumes more than half of India's overall defence budget, with the majority of expenditure going into cantonment maintenance, pay, and pensions rather than crucial equipment and ammunition. The Indian military budget, or defence budget, is the percentage of the Union budget allocated to the funding of the Indian Armed Forces. The military budget pays for staff salaries and training, equipment and facility upkeep, support for new or continuing missions, as well as the development and acquisition of new technology, weapons, equipment, and vehicles.

The Indian Army consumes more than half of India's overall defence budget, with the majority of expenditure going into cantonment maintenance, pay, and pensions rather than crucial equipment and ammunition.

On February 1, 2020, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented her second and the Narendra Modi Government's seventh regular budget. She allocated Rs. 4,71,378 crore (US$ 66.9 billion1) to the Ministry of Defence (MoD), emphasising that national security is a key priority of the government. The Ministry of Defence's total allocations include Rs. 3,23,053 crore ($45.8 billion) for the Defence Services Estimates (DSE), an annual publication of the Ministry of Defence's finance wing that primarily covers the expenses of the three armed forces and the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO), and is widely regarded as India's defence budget. The remaining funds are allocated between defence pensions (Rs. 1,33,825 crore or $19.0 billion) and the Ministry of Defence (Civil) (Rs. 14,500 crore or $2.1 billion). Overall, the MoD's allocation increased by 9.4 percent, amounting to an increase of Rs. 40,367 crore. This begs the question of how this increase would impact India's defence and modernization efforts in particular.

Advertisement

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with chief of defence staff General Bipin Rawat (left) and army chief General M.M. Naravane (right) during in his visit to Ladakh in July 2020. Photo: PMO

This budget represents just 1.7 percent of GDP, which is insufficient to modernise the military in light of perceived threats from China and Pakistan, particularly in the aftermath of Afghanistan's independence with the Taliban in charge.

Between 2016 and 2020, India became the second-largest importer of weaponry, accounting for 9.5% of worldwide imports. Between 2011-15 and 2016-20, India's arms imports decreased by 33%, according to a research released by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri), at a time when the government has adopted a slew of measures to reduce its reliance on imported military hardware.

The new companies now have a Rs 65,000 crore order book. These orders were previously scheduled to be fulfilled and have been transferred to the new entities.

To increase India's defence sector self-sufficiency, the Ordnance Factory Board (OFB) was divided into seven distinct firms. On the auspicious occasion of Vijayadashmi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi dedicated these seven firms to the nation. The new Defence PSUs are wholly owned by the government and will contribute to the country's increased self-reliance in terms of defence preparedness.

The seven new entities began operations on October 1, 2021. Troop Comforts Limited (TCL); Yantra India Limited (YIL); Gliders India Limited (GIL); India Optel Limited (IOL); Advanced Weapons and Equipment India Limited (AWE India); and Armoured Vehicles Nigam Limited are the newly formed companies (AVANI).

Advertisement

Pic: OFB

Prime Minister Modi paid tribute to Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, stating that Dr Kalam had devoted his life to the cause of a strong nation. "Restructuring the Ordnance Factories and establishing seven new enterprises will bolster his vision of a strong India," the Prime Minister continued. According to him, the new enterprises are part of the numerous resolutions that the government has been pursuing to help people establish a new future, and they will play a critical role in import substitution, in line with the vision of 'Atmanirbhar Bharat'.

The new companies now have a Rs 65,000 crore order book. These orders were previously scheduled to be fulfilled and have been transferred to the new organisations. In his presentation, the Prime Minister referenced the Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh Defence Corridors as examples of the new strategy. According to the Prime Minister, defence exports have increased by 325 percent over the previous five years, and policy changes have created new prospects for youth in MSMEs.

In the twenty-first century, because any firm or nation's growth and brand value are determined by its R&D and innovation, he made a plea in his address to new companies to take the lead in future technologies. These new businesses enjoy complete functional autonomy and safeguard the interests of their employees.

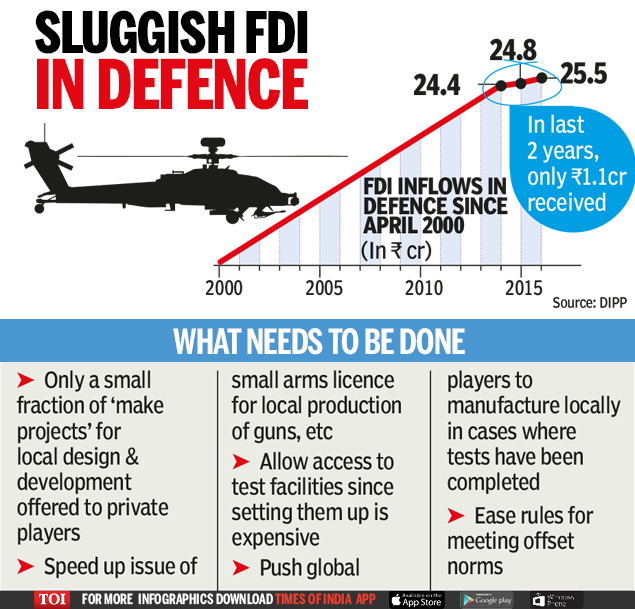

In May 2020, the Centre announced an increase in the automatic route FDI limit in the defence sector from 49 to 74%.

According to Defence Minister Raj Nath Singh, the government's decision to establish new enterprises demonstrates its commitment to Atmanirbhar Bharat. And he stated the reorganisation of the OFB's mission as follows: "It is to restructure the Ordnance Factories to improve product expertise; lucrative and productive assets; self-reliance; cost effectiveness and quality; and competitiveness."

He also reaffirmed the government's commitment to developing India as a powerhouse for defence industry and a net exporter. This can be accomplished through the private sector's active participation, the establishment of defence production units, and the formation of joint ventures. According to the defence minister, "the public and private sectors are collaborating to strengthen the armed forces' readiness."

The members of the Society of Indian Defence Manufacturers (SIDM) expressed their delight at the establishment of seven new firms and indicated their want to do business with them. These new businesses will adhere to corporate standards in all aspects of their operations. Tendering, contracting with payment systems, and vendor development are all included in this.

Advertisement

Credit: TOI

In May 2020, the Centre announced an increase in the automatic route FDI limit in the defence sector from 49 to 74%. The administration has emphasised the importance of strengthening indigenous defence manufacturing. The Ministry of Defence has set a target of $25 billion (Rs 1.75 lakh crore) in defence manufacturing revenue by 2025, which includes a $5 billion (Rs 35,000 crore) export target for military gear.

The delay in announcing the corporatization of 41 ordnance factories is understandable, considering their age and the strong and entrenched unions representing their 81,500 employees.

According to the SIPRI 2021 study, India has the dubious distinction of being the second highest importer of conventional armaments (9.5%).

The government's present structure is notably different, as the four proposed public sector enterprises (PSUs) will continue to manage gliders, parachutes, optics, components and ancillaries, and troop comfort items. This will perpetuate substandard quality, delays, and excessive prices for products that may readily be purchased at a lower cost and higher quality from private players. While this strategy made sense during the world wars, when the private sector's competence was limited, India's post-1991 focus on liberalisation, privatisation, and globalisation requires that it discontinue manufacturing these low-tech, non-strategic items in captive ordnance factories.

While Kelkar's level playing field doctrine has attracted companies such as L&T, Mahindra & Mahindra, Godrej & Boyce, Tatas, and a number of IT firms, the paltry 26 per cent FDI has hardly enticed any major OEM to establish a manufacturing base in India. In 2006, the government launched an offset programme to utilise India's large-scale acquisitions in order to secure outsourcing, export orders, and crucial technologies from major global defence manufacturers. Except for a few outsourcing orders for low-tech items, the experience thus far has been poor.

Advertisement

Pic: LCA Tejas

Despite these initiatives, India's military industry remains underdeveloped, and the private sector is still not considered a partner in the country's quest for greater self-reliance. The much-hyped indigenous Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) is powered by a GE 404 engine from the United States, while the radar is manufactured by ELTA in Israel. The development of the Kaveri engine by the Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE) has been a complete failure. German MTU engines power the indigenous Main Battle Tank (MBT). Despite the huge increase in FDI, inflows totaled only $300 million between April and September 2020. This is partly because of the numerous caveats attached to the 76 percent FDI cap.

According to the SIPRI 2021 study, India has the dubious distinction of being the second highest importer of conventional armaments (9.5%). In 1993, the Kalam Committee estimated our Self Reliance Index (SRI) at 30%, with a goal of increasing it to 70% within a decade. The committee identified several critical subsystems, including the focal plane array, passive seekers, stealth, AESA radar, RLG, and carbon fibres, for which India's design and development quality must be significantly improved. Weapons, propulsion, and sensors continue to be the primary stumbling blocks for India's design competence in the DRDO, and India's SRI has made no progress.

Clearly, the government prefers the private sector. The ToT contract with Tatas rather than HAL for the construction of 40 C-295 transport aircraft was a significant development.

Since 1963, technology transfer has been a significant component of India's strategy mosaic for developing major systems and platforms (in the aftermath of the MiG-21 aircraft). HAL has been manufacturing the Sukhoi Su-30 in accordance with Russian technology transfer documents. The T90, manufactured in the Avadi tank factory using technology obtained from Russia, follows a similar path. This demonstrates that manufacturing is based on imported rather than local design. The standard argument against defence PSUs is that they are better integrators of imported subparts than actual makers. It's unsurprising that HAL's value addition to Su-30 manufacture is less than 20%.

The primary issue confronting the OFB is not a lack of autonomy or accountability, but a lack of resources to enhance capabilities. OFB spends less than 0.7-0.8 percent of its revenue on research and development. The other significant drag has been investment on new capital, which accounts for less than 1% of revenue. Additionally, capital spending accounts for only 3-5 percent of total expenditure. While ordnance companies have a well-managed renewal and replacement budget for obsolete machines, they invest very little in cutting-edge capital and machinery.

Corporatization of the OFB must be viewed in the broader context of India's military industry capability, self-reliance quotient, design capability in critical systems and their quality, timeliness, and cost-effectiveness, as well as the involvement of private players in defence manufacturing as partners alongside OEMs and design houses. The transition from the MMRCA transfer of technology (ToT) contract with HAL (buy and make) to directly purchasing aircraft from Dassault Aviation in France demonstrates how HAL has failed to achieve both user and ToT partner expectations.

Clearly, the government prefers the private sector. A significant development has been the award of the ToT contract to Tatas rather than HAL for the construction of 40 C-295 cargo aircraft. This is the first time a private corporation has accessed a significant ToT. The DRDO cannot exercise monopoly power over research. The private sector, academia and reputed design houses must be part of this process, which will improve India’s design capability significantly.

Advertisement