At Starbase, SpaceX first Starlink V2 satellites were spotted.

Thursday, July 21, 2022 | Chimniii Desk

On Monday, SpaceX was seen putting several of the first Starlink V2 satellite prototypes into a special device made to fill the payload bay of the Starship.

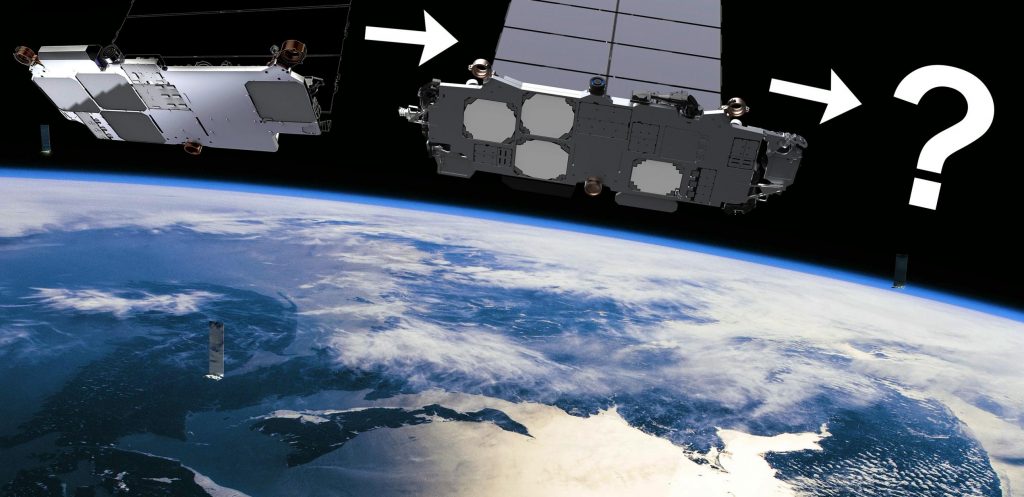

Though SpaceX has utilised the dispenser before, photographer Kevin Randolph's images are the first to unmistakably reveal actual prototypes of the upcoming Starlink satellites. These Starlink Gen2 or V2 satellites will be "at least 5 times better," "an order of magnitude more capable," and around four times heavier than existing (V1.5) Starlink satellites, according to CEO Elon Musk.

The new satellite bus design has the potential to significantly increase the viability and cost-effectiveness of SpaceX's Starlink constellation when combined with Starship's enormous fairing and lift capability. However, the business must first launch and qualify models of the new satellite design and ensure that all related ground support machinery functions as intended.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The ground support hardware and the general route each satellite will take from its arrival at the launch facilities to liftoff on a Starship are wildly different from anything done before due to the designs SpaceX has chosen for both Starlink V2.0 satellites and the Starship hardware that will deploy them in orbit. The images from July 18th (as well as screenshots from a recent factory tour) demonstrate that the new satellites are essentially enlarged versions of their smaller counterparts, which are similarly narrow rectangles.

The new spacecraft is about seven metres long and three metres broad (23′ x 10′) instead of roughly 3m x 1.5m (10′ x 5′), although it has a fairly similar aspect ratio. They supposedly weigh 1,250 kilogrammes compared to the V1.5's estimated 310 kilogrammes (2,750 lb vs. 680 lb), and they also seem to be roughly twice as thick. The V2.0 bus will therefore have roughly 7–10 times more usable volume than the V1.0 and V1.5 buses. The fact that each new satellite might provide almost a magnitude more useful bandwidth shouldn't come as a surprise.

Advertisement

Advertisement

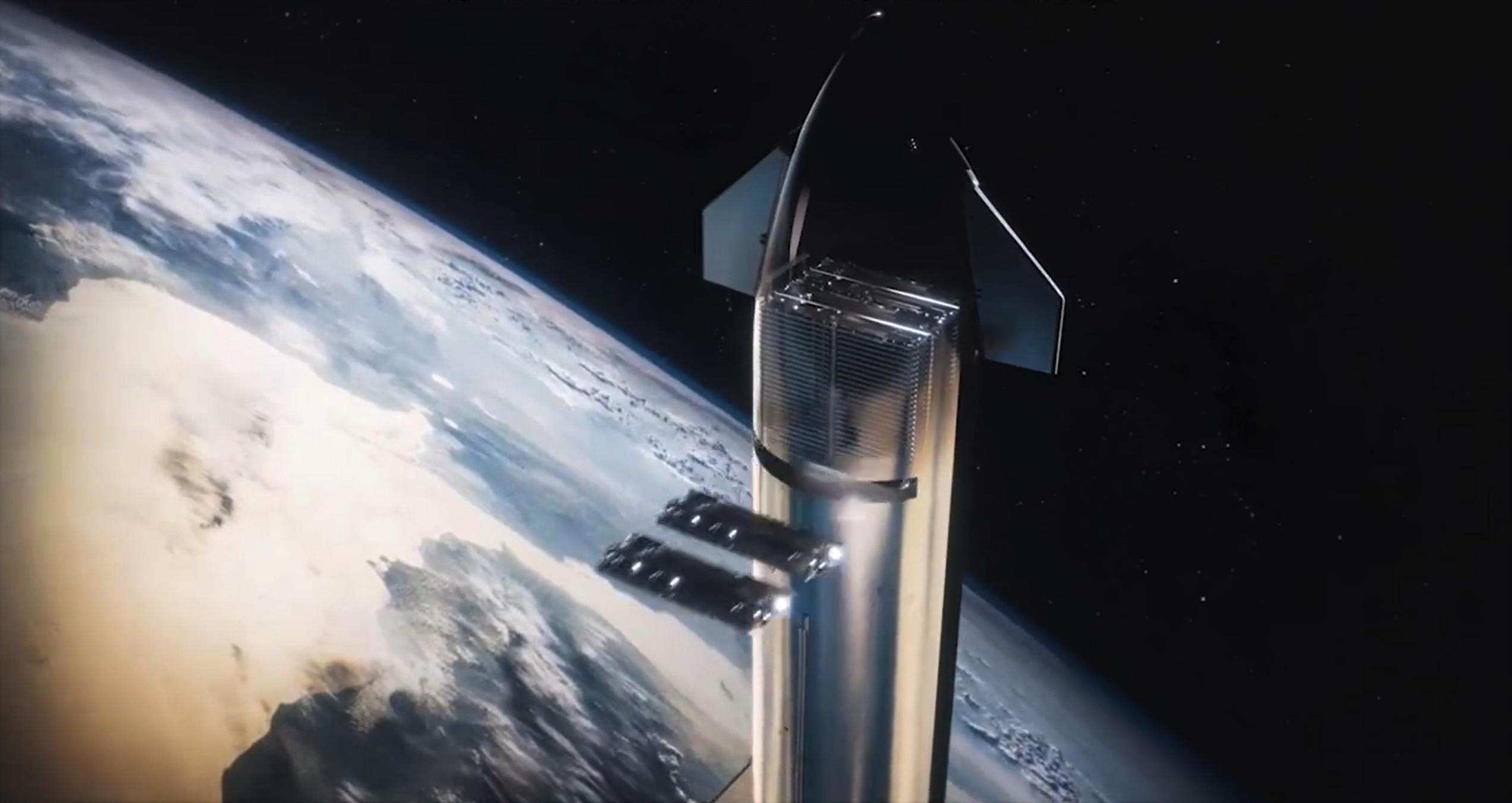

Starlink V2.0 constellation deployment would be at least twice as cost-effective to execute even if Starship could only launch the same mass (16 tonnes) as Falcon 9. Assuming that Starship launch costs are roughly the same as Falcon 9's and that Starship can only launch a similar 50–60 satellites at once, an almost 10-fold performance improvement from a satellite that only weighs five times as much relative to V1.5 would make Starlink V2.0 constellation deployment. In reality, according to a recent SpaceX rendering, Starship will initially be able to transport 54 Starlink V2.0 satellites.Therefore, even though Starship will cost about $75M to launch, five times more than Falcon 9, it will still be less expensive per unit of bandwidth launched. The cost of Starlink launches (excluding satellite cost) should decrease from approximately $15,000 per gigabit per second (Gbps) to around $1,500-2,500 per Gbps depending on individual satellite bandwidth if Starship finally hits marginal launch costs as low as Falcon 9 ($15M).

The network's overall cost will be greater and based on more factors, but the combination of Starship and V2.0 satellites may eventually result in a 5–10 fold decrease in the relative cost of Starlink launch operations. These savings will grow if Starlink V2.0 satellites are truly less expensive to produce than V1.5 satellites per unit of throughput once mass production starts, which is not improbable. The equation might even turn out to be more advantageous if Starship can develop swiftly and become completely and effectively reusable.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Although it won't be a simple task, loading Starship with satellites will increase complexity and danger significantly compared to the procedures SpaceX now employs for Falcon 9 Starlink launches. The early SpaceX Starship payload bay design is a roughly square box that fits slightly below the ship's inwardly curved nosecone and above its highest tank dome. It can store up to 54 Starlink V2.0 satellites and can dispense pairs of satellites through a relatively narrow payload bay door that is only wide enough for the task at hand, according to a render of the mechanism released last month. The mechanism is about nine metres (30 feet) tall and eight metres (26 feet) wide.

The airframe of a starship is almost entirely welded together. The dispenser door or a further smaller human-sized access port are the only ways to enter the payload bay once the nosecone and payload bay have been mounted on top of a ship. The solution proposed by SpaceX is to construct a transportable satellite storage container that can be raised several hundred to thousands of feet above the ground using a crane or launch tower arms, and to load satellites into the container in reverse using the payload bay's own dispenser mechanism. It's not simple, even though it shouldn't sound that way.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The fact that SpaceX appears to have used some of the initial Starlink V2.0 prototypes to practise that procedure is fantastic. Several satellites were seen being loaded into the sole "loader" inside one of Starbase's three major production tents in pictures taken on July 18. The incredibly long and thin satellites were hoisted using a load-spreader device, which was likely necessary to prevent them from bending too much in the centre during the lift. It's unclear if SpaceX is genuinely installing satellites well in advance for loading onto a Starship prototype, or if it's just practising the procedure.

The satellite loader has already greeted Starship S24 once, possibly to load a prototype or mockup before ground testing started, while it is currently undergoing preflight testing. Starship S25's nose and cargo bay section are far closer to completion than the rest of the ship, which appears to be at least a month or two away.

Advertisement